A commercial jet boat lost control, crashed into trees. Injuries to two of the twelve persons on board. Jet boat engine failed, so no steering. All due to a single failure in an engine control fuse that broke from metal fatigue. The fuse box, bolted to the engine, was vibrating too much. TAIC recommends urgent action to address risks associated with single points of failure.

Executive summary Tuhinga whakarāpopoto

What happened

- On 21 March 2021, the jet boat KJet 8 (figure 1) was travelling on the Shotover River (figure 2) with a driver and 12 passengers on board. As it rounded a right-hand bend the engine stopped and as a result the driver lost control of the jet boat.

- It continued moving forward under its own momentum and collided with a low overhanging branch of a tree on the bank of the river.

- The driver and one passenger were struck on the head by an overhanging branch and received moderate head injuries. They were airlifted to hospital and discharged the same day.

Why it happened

- A fuse within the engine control system failed resulting in the engine stopping.

- As a consequence of the engine stopping, propulsion and steering was lost, and the driver was unable to control the jet boat.

- Examination of the failed fuse showed that it is virtually certain the fuse failed as a result of mechanical fatigue caused by vibration. The fuse and its connections into the main fuse box were replaced and the engine started and operated successfully.

-

The cause of the accident was a single point of failure in a critical jet boat control system, which resulted in total loss of control of the jet boat. The single point of failure had not been identified by the operator as part of a risk mitigation process and therefore the Commission has made a recommendation to the Director of Maritime New Zealand (MNZ) that:

They engage with operators working under Maritime Rules Part 82 to identify jet boat systems which carry the risk of single point failure that would result in a total loss of control of the jet boat, and discuss possible measures that could be taken to reduce the risk to passengers and crew to as low as reasonably practicable.

What we can learn

- To prevent similar component failures in the future requires that an operator conducts a thorough and robust assessment of a jet boat operating system and identifies appropriate mitigation measures. Specifically, in relation to this incident by ensuring that the flexing of wires cannot apply a mechanical load to the fuses and that fuse boxes are mounted in such a way that they are not subject to the direct vibration of something as significant as an engine.

Who may benefit

- The commercial jet boat industry, recreational jet boat owners, the regulator MNZ, the wider marine industry and boat builders.

Factual information Pārongo pono

Narrative

- On 20 March 2021, the day before the accident, the single-engine jet boat KJet 8 was on a return trip and approaching the road bridge before entering Lake Wakatipu. The driver, in accordance with local requirements, switched off the engine and stopped the boat.

- Shortly afterwards the driver attempted to re-start the engine, but it would not start. The driver made a radio call to the Kawarau Jet Service Holdings Limited (KJet) Marine Base (term for the location of workshops and overnight storage facility) (figure 3) and requested assistance before checking the battery terminals in the engine compartment.

- The driver attempted to start the engine an additional four or five times before the engine finally started. The driver then continued the trip back to the pier at Queenstown to offload the passengers.

- KJet 8 was taken out of service for the rest of the day. It underwent diagnostic checks but there were no faults registered. The boat was successfully started several times before being returned to the Marine Base overnight.

- At about 0825 on 21 March 2021, the driver of the KJet 8 arrived at the Marine Base and checked the hazard board for any potential new route hazards before launching the boat into the water.

- The driver carried out initial checks using prompts contained on a checklist. On completion of the checks the driver took KJet 8 from the Marine Base to the main pier in Queenstown.

- At about 1000, KJet 8 departed on its first trip with 11 passengers on board. It returned 55 minutes later and there were no reported deficiencies with the boat.

- At about 1100, KJet 8 departed on its second trip of the day with 12 passengers on board. The outbound trip proceeded up the Kawarua and Shotover Rivers (figure 3), turning around at approximately 1135 and heading back down the river. Approaching a right-hand bend, the driver recalled not hearing any engine noise and the boat levelled out, lost steerage and continued to travel straight ahead.

- The driver was unable to regain control of the jet boat and shouted to the passengers to “get down” just before being struck on the head by an overhanging branch from a tree. KJet 8 came to a halt when it became entangled in a tree on the riverbank.

- At about 1140 the Marine Base received a radio call from a passenger on board KJet 8 requesting “help, help, help”. The deputy operations manager spoke with the passenger who confirmed that they were calling from KJet 8 and that the driver had been injured.

- The passenger informed the deputy operations manager that the boat was located “close to some bridges”.

- At about 1142, KJet 1 departed the Marine Base en route to assist KJet 8.

-

At 1154, KJet 1 arrived at the scene. Its crew located KJet 8, assessed the scene and commenced first aid for the driver and passengers. The driver and one passenger appeared to have moderate head injuries, later diagnosed at the hospital, including a minor concussion.

Figure 3: Location of the accident and key route positions (Credit: Google Earth) - At about 1200, the passengers were assisted from the boat and onto the riverbank.

- At 1211, it was confirmed that a rescue helicopter was at the scene, and by 1230 the driver of KJet 8 and the injured passenger were on board and en route to the local hospital. They were released later the same day.

- The remaining 11 passengers were transferred to other jet boats and returned to the operator’s base where they were assessed by paramedics. Some passengers were treated for minor injuries before being released.

- On completion of the passenger rescue, KJet 8 was released from under the branch of the tree. It was floated downstream to a nearby bridge and recovered onto a road trailer and transported back to the Marine Base. An attempt had been made to start the engine, but it was unsuccessful.

Personnel information

- The driver of KJet 8 held a Jet Boat Driver Commercial Licence (issued by MNZ) on 23 January 2015, which was valid for 10 years.

- The driver also held a Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency DL9 driver licence medical certificate issued on 19 December 2014, as required for the role, which had expired on 19 December 2019. An application for a new certificate had been made on 26 February 2021. The driver also held a current Workplace First Aid Certificate valid until 17 September 2021.

- The driver commenced employment with KJet in 2012 and had nearly 1600 hours of driving experience. They had undergone audited driver refresher training on 16, 18 and 20 March 2021.

Vessel information

- KJet 8 was a 6.5 metre jet boat built by Mackraft in Bluff, New Zealand. It was initially inspected in 2003.

- It had a maximum speed of 95 kilometres per hour and a total seating capacity of 13, permitting 12 passengers and a driver to be seated.

- It was powered by a marinised single petrol-driven 6.2 litre Direct Injection V8 Kodiak engine (originally a Chevrolet model designed for a road vehicle, but which had been marinised by KEM Equipment and sold as a Kodiak engine) supplied by KEM Equipment based in Oregon, United States of America (USA) (figure 4 – left). On 31 March 2021, the engine running hours totalled 1311. Propulsion was provided by a Hamilton Jet type 212 jet unit (figure 4 – right).

Meteorological and ephemeral information

- At 1100 on 21 March 2021, the temperature was 12°C and there was a 2 kilometre per hour southerly wind. Visibility was approximately 20 kilometres.

Site and wreckage information

- The accident occurred on the return leg of the journey, travelling downstream approaching a right-hand bend. Figure 5 shows the point of impact with the tree branch situated on the left-hand bank. The jet boat suffered minor structural damage.

The operator

- At the time of the accident the operator, KJet was a privately owned adventure tourism business based in Queenstown, New Zealand. Operating since 1958, the company was the world’s first commercial jet boat operator.

- Passengers board alongside the main town pier in Queenstown and are taken for a jet boat ride on the Kawarau and Shotover Rivers, returning to Queenstown about 60 minutes later.

- KJet operated eight commercial jet boats.

How a jet boat works

- A jet boat is propelled and steered through the water by a jet unit (figure 6). The jet unit is an impeller water pump powered by the jet boat’s internal combustion engine.

- The pump sucks water in through an intake under the hull and forces it out through a pipe and steering nozzle mounted on the transom, thereby providing thrust to the boat.

- The steering nozzle can be rotated either side using the driver’s steering wheel to direct the thrust and provide steering.

- A bucket-shaped deflector is attached to the unit, which can be lowered down over the end of the steering nozzle. The deflector redirects the water jet forwards, which provides reverse thrust. The deflector is named the ‘reverse bucket’ and is lowered using a lever located beside the driver’s seat.

Tests and research

Diagnostics

- After the passengers had been evacuated from the scene of the accident, KJet mechanics used diagnostic equipment to try and identify the cause of the engine stopping without any warning. The diagnostic equipment detected a ‘Powertrain Relay Contact Fault’ (figure 7).

- Once the Commission had opened an inquiry into the accident, Commission investigators worked with KJet engineers to oversee the process of diagnosing the causes and circumstances of the engine failure.

- The information from the diagnostic read out provided engineers and investigators with a focal point from which to systematically try to identify the cause of engine failure. During examination of the engine, its components and the powertrain, it was found that deliberate movement of the wiring loom connected to the main engine fuse box (figure 8) caused the powertrain relay to activate.

- Closer inspection of the fuse box found that a 20 ampere fuse protecting the engine powertrain relays had failed. The fuse and the connections into the main fuse box were replaced, the engine was retested and it operated successfully.

Independent examination

- Following the initial findings of the investigation that a single 20 ampere fuse had contributed to the engine stopping without warning, the Commission appointed Quest Integrity NZL Limited (Quest Integrity) to examine the fuse from KJet 8 and help determine the exact cause of the failure.

- Essentially two modes of possible failure were examined – electrical overload and mechanical fatigue.

- There was significant evidence to show that the fuse did not fail as a result of electrical overload as shown in figure 10. Extensive melting did not occur, the fuse section was not distorted, and failure did not occur in the normal mid-point position of the fuse (figure 9).

- It was considered very likely that the fuse failed primarily because of bending fatigue due to flexing caused by an unsupported connecting wire. Evidence to support this hypothesis included: lack of gross distortion, a flat fracture face, failure occurring at the end of the radius where there was a stress concentration, the design of the fuse box, and stiff connecting wires allowing a rotation of about 10 degrees.

- The fuse was made from zinc, which provided reasonable corrosion resistance, low melting point, good electrical conductivity and relatively low cost. Zinc is not a good structural material. It is hard and brittle and will be highly prone to fatigue failures at room temperature. It is therefore important that the wires connecting to a fuse box should not be able to transfer cyclic loading to the fuse, which would lead to fatigue.

- The fuse box fitted to KJet 8 was of a design commonly used in the automotive industry where wiring looms are generally secured to prevent significant vibration occurring on the wiring. When KJet 8’s engine was marinised the fuse box was installed on a bracket bolted to the engine without any vibration dampening. Without vibration dampening the fuse box was subject to vibrations from the engine, which could lead to fatigue loading on the fuse box assembly. Wires were bent into place after they were fitted into the fuse box.

- If the resonant frequency of a wire assembly is close to one of the engine’s vibrational frequencies, resonance will occur that could result in significant vibrational movement and increased risk of failure of the weak points, such as a fuse. In this case it is considered probable that the wire to the failed fuse had a longer unsupported length than the other wires (figure 11), which likely resulted in excessive vibration contributing to the mechanical failure of the fuse.

Conclusions of Quest Integrity's examination

- The report by Quest Integrity made the following conclusions (quoted):

- The fuse in KJet 08 probably failed as a result of mechanical fatigue as a result of the connecting wiring flexing due to resonant vibration. This resulted in wear/damage to the fuse support hole and a straight flat fracture at the location most prone to bending fatigue.

- The fuse in KJet 08 did not fail as a result of electrical overload.

- The fuse in KJet 08 did not fail as a result of a mechanical overload, i.e. it did not fail as a result of the accident.

- The fuse box/wiring assembly/support structure was not ideal to prevent failure as a consequence of the following:

- The fuse box will have seen significant vibration as it was mounted in a stiff bracket that was directly bolted to the engine in the jet boat.

- Unsupported wiring could flex backward and forward as a result of resonance.

- The fuse box was not ideal in that the flexure of the wires could introduce significant torsional movement on the legs of the fuses and the fuses were made of zinc. Ideally it should not be possible for the movement of the wires to cause any movement in the legs of the fuses.

Previous occurrences

- The Commission has been unable to find a previous occurrence of a jet boat engine failure caused by a fuse subjected to mechanical fatigue or electrical overload. There were no reported cases found in the international jet boat community nor any contained in the MNZ accident database.

- The Commission also contacted the Transportation Safety Board of Canada, a country where jet boating is well established, to gauge how systemic this type of occurrence might be. Their accident database contained 208 cases of water jet propulsion system occurrences. Of these 208 only three were engine failures, but none were as a result of a fuse being subjected to mechanical fatigue or electrical overload.

- KEM Equipment, the company in the USA responsible for marinising KJet 8’s engine, was also contacted to establish whether they had received reports about mechanical fatigue of fuses or loss of power caused by the excessive vibration of the wiring assembly. This occurrence was the first incident brought to their attention.

- Inspection of KJet’s own incident log showed that there were 37 incidents recorded between 1 March 2020 and 31 March 2021. Of these, six were recorded as electrical incidents, but none were related to fuses or wiring assembly.

Industry regulation

Maritime Rules Part 80

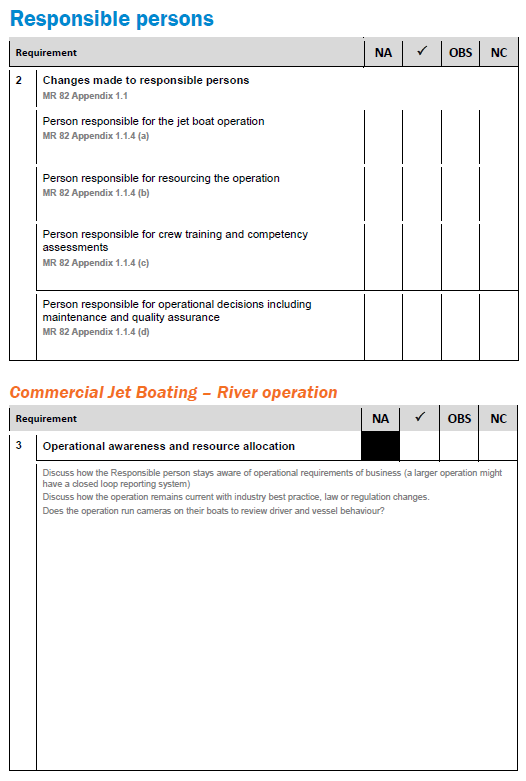

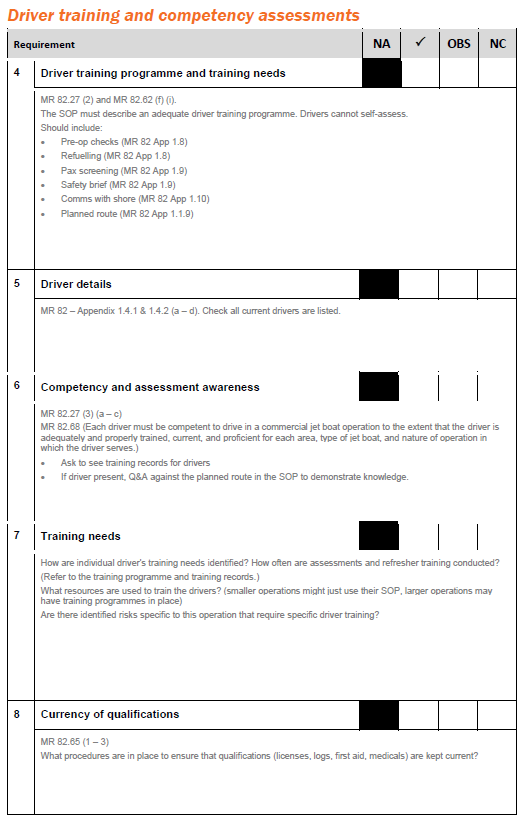

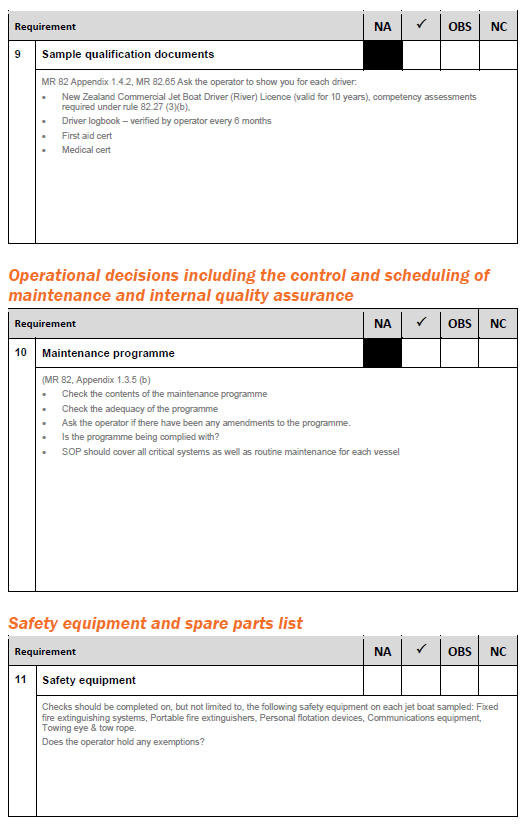

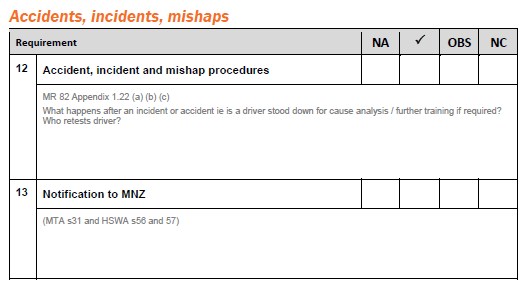

- Maritime Rules Part 80: Marine Craft Involved in Adventure Tourism came into force in August 1998 and was superseded by Maritime Rules Part 82: Commercial Jet Boat Operations – River in August 2012. Part 80 incorporated codes of practice for various types of marine craft used in the adventure tourism industry, including commercial jet boats on rivers.

- Part 80 required, in part, that the operator ”draw a safe operational plan related to the specific operations of the owner’s boat or boats”. Part 80 laid out various requirements that the Safe Operational Plan (SOP) must address, including a planned maintenance schedule and operational checks of the vessel.

-

Two jet boat accidents occurred in 1999 (MO-1999-213 Jet boat Shotover 15 collision with canyon wall, Shotover River, Queenstown, 12 November 1999 and MO-1999-212 Jet boats Shotover 14 and Shotover 15 separate collisions with canyon wall Shotover River, Queenstown, 21 October and 12 November 1999). The Commission investigated the accidents and made 15 recommendations. One of the recommendations was directed at Part 80 and is relevant to this inquiry:

…a change to Rule Part 80 that will require commercial jet boat operators to identify on each jet boat all components that are critical to the safe operation of the boat, and to have a documented inspection and maintenance system in place that covers those critical components. The inspection and maintenance system should complement rather than replace any system of daily checks. (104/99)

With the change to Part 80, there was an expectation from the Maritime Safety Authority (the Maritime Safety Authority was the predecessor to MNZ) that operators would address this issue in their own SOP. Maritime Rules Part 80 was subsequently superseded in 2012 when Part 82: Commercial Jet Boat Operations – River came into force.

Maritime Rules Part 82

-

Part 82 did not explicitly address recommendation 104/99. However, it included a section ‘Managing hazards’ (Appendix 2), which refers the jet boat operator to ”its health and safety responsibilities under the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992, by including, without being limited to, the following [in part]:

(a) the process used by the operator to identify the operational hazards that may cause harm to a person; and

(b) the process used by the operator to review operational hazards and how they are to be controlled, including how drivers are made aware of new hazards before drivers and passengers are exposed to them (for example, the day-to-day changes in river conditions); and…

(c) the process for reporting significant hazards, accidents, incidents, and mishaps;

and…”

-

On 23 February 2019, the Commission opened a further inquiry into a commercial jet boat accident (Marine inquiry MO-2019-201, Jet boat Discovery 2 contact with Skippers Canyon wall, 23 February 2019), which involved one passenger suffering a significant injury and eight passengers minor injuries when a jet boat’s steering failed and it made contact with a rock face.

The subsequent report recommended to the Director of MNZ that:

They ensure all operators working under Maritime Rules Part 82 have identified on each jet boat all systems that are critical to the safe operation of the boat, and to have a documented inspection and maintenance system in place that covers those critical systems and also ensures they meet manufacturers’ specifications. The inspection and maintenance system should complement rather than replace any existing system of daily checks. (010/19)

Maritime NZ's response to recommendation 10/19 was in part:

Maritime NZ agrees with this recommendation...

Maritime NZ is currently developing a programme to extend areas within an operation that are audited under Part 82 requirements. The audits will be covering a wide range of topics but will specifically cover two key items:

-

The adequacy of the driver competency programmes required by the rule, and checking that they have been properly implemented by each operation.

-

The adequacy of the maintenance programmes required by the rule, and checking that they have been properly implemented by each operation.

As part of this programme of work Maritime NZ is also exploring working with commercial jet boat operators to develop critical systems maintenance guidance.

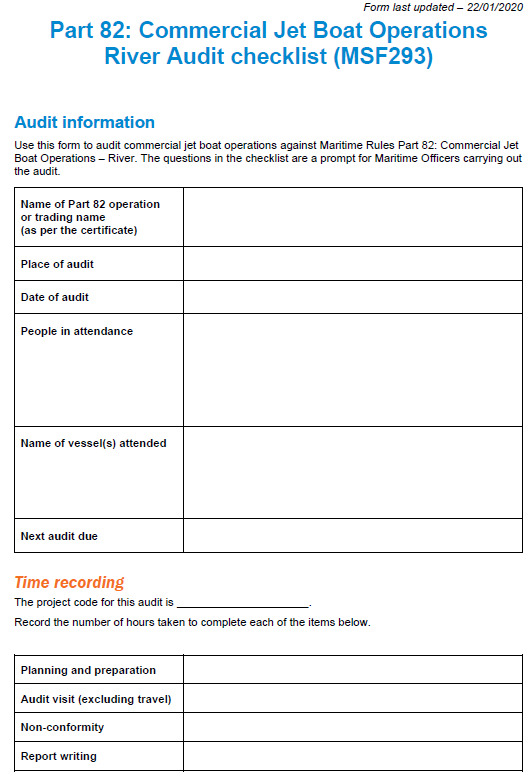

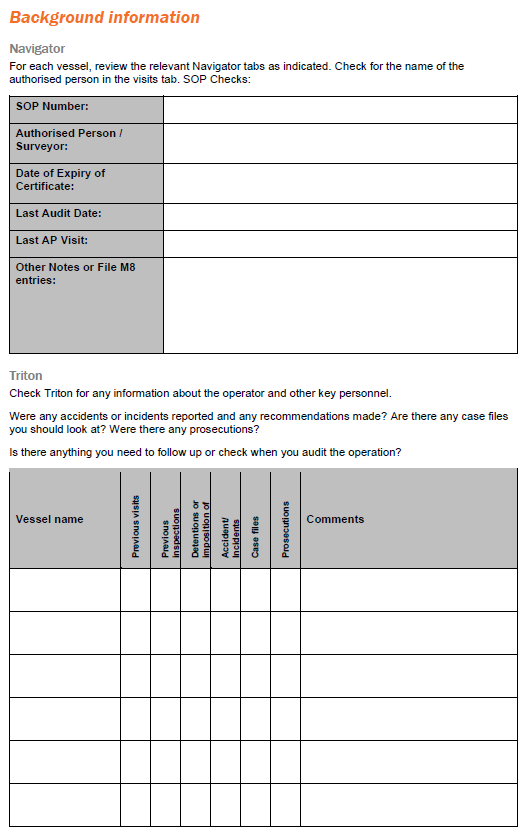

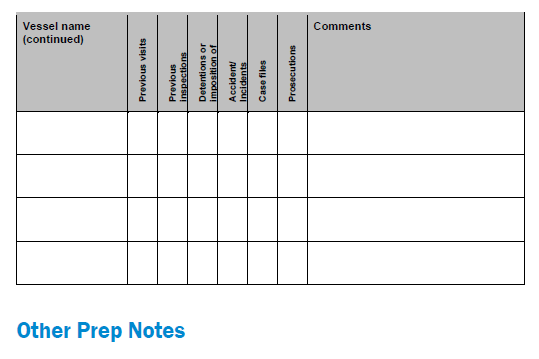

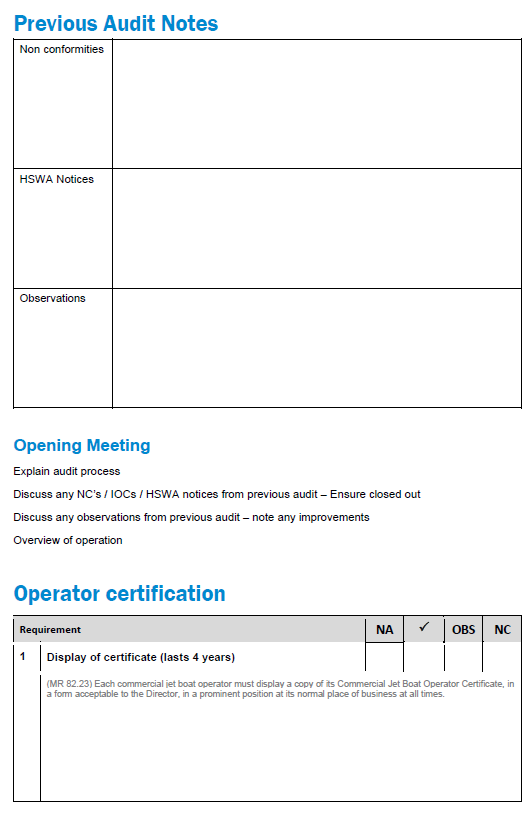

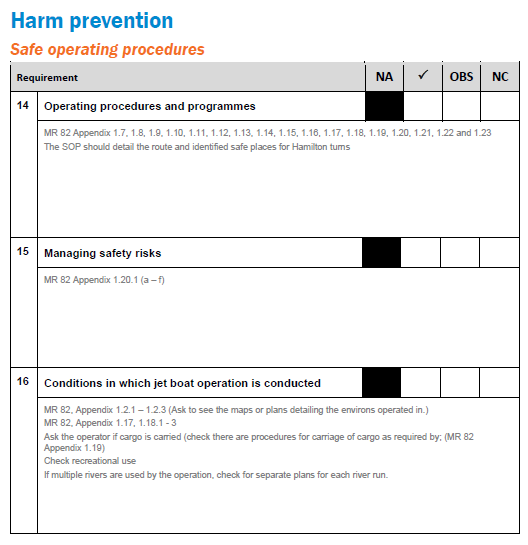

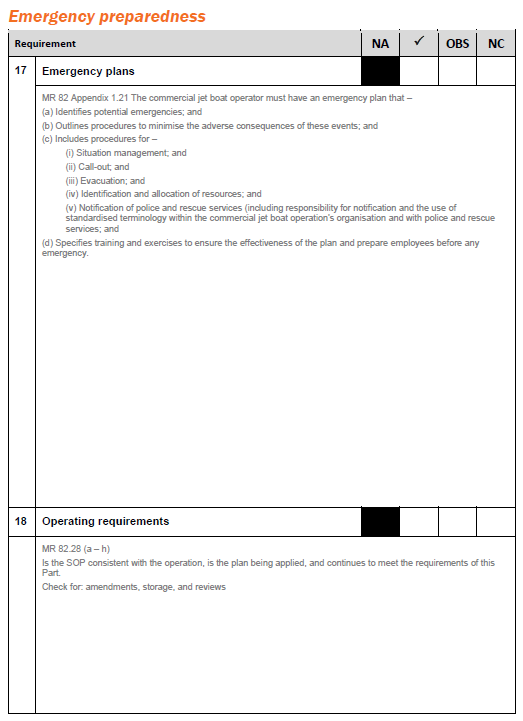

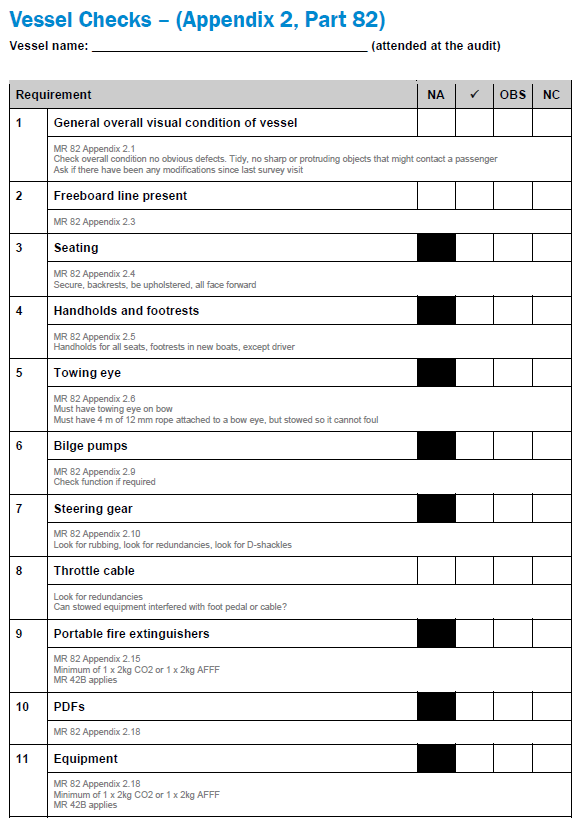

- In 2020, the responsibility for auditing operator’s SOP was transferred from a third party to MNZ and an audit checklist for Part 82 was introduced. The checklist can be seen in Appendix Part 82 Audit Checklist (MSF293). The maintenance section of the audit checklist (figure 12) mentions “critical systems” as a checklist item, although that term is not defined. MNZ’s work in this area is ongoing.

Maintenance and inspection

Maritime New Zealand (MNZ)

- In accordance with Part 82 of the Maritime Rules, Kawarau Jet Service Holdings Limited (operating as KJet) were issued with a Jet Boat Operator Certificate on 13 December 2019. The certificate was valid until 28 September 2022 subject to audits required in accordance with section 54 of the Maritime Transport Act 2013 and the requirements of Maritime Rules Part 82 being met.

- The Jet Boat Operator Certificate showed that the boats being operated had been inspected, the operator’s SOP had been approved, and the operation had been audited and found to be in accordance with the Code of Practice for the Safety of Jet Boats Operating on Rivers (Appendix 1 of Part 82 of the Maritime Rules).

- The audit conducted on 23 September 2019 found that pages 26 and 27 of the SOP showed that the operator had applied a maintenance programme for every commercial jet boat and propulsion unit.

- The most recent MNZ inspection check sheet for KJet 8 was dated 21 October 2020, and the inspection found the jet boat ‘Fit for Purpose’ and there were no deficiencies.

The operator

-

Section 4 of the SOP described the planned maintenance requirements, namely:

All boats are checked and maintained on daily and weekly basis. As well as these routine checks, they are also maintained according to the operational hours they have had. The forms used for these checks are listed below:

KJet Daily Checklist Spanner Check Sheet A Spanner Check Sheet B

Spanner Check Sheet A

Spanner Check Sheet B

Spanner Check Sheet C

KJet Spanner Check Log.

- Relevant to this accident the check sheets describe the checks required on the engine, jet unit and electrical system.

- Examination of servicing records for KJet 8 between January 2020 to March 2021 showed that the servicing requirements as defined in the SOP had been carried out.

Analysis Tātaritanga

Introduction

- At the time of the accident the commercial jet boat KJet 8 was operating on the Shotover River and there were 12 passengers and a driver on board. Common with this type of adventure activity the vessel was proceeding at high speed down the river when the engine stopped and control of the boat was lost.

-

The boat impacted with a low overhanging tree branch on the bank of the river. One passenger and the driver were airlifted to hospital with head injuries and some other passengers suffered minor injuries.

- Commercial jet boating can be a high-risk activity and in the event of an accident the consequences can be severe. The Commission has opened several inquiries and made recommendations to help improve jet boating safety. Jet boat operators (including KJet) have been proactive around improving safety systems and MNZ have improved the regulatory environment.

- At the time of the accident, KJet 8 was on its return journey and approaching a right-hand bend in the river when its single engine stopped. The petrol-driven engine required a constant power supply to operate. However, the failure of a 20 ampere fuse resulted in a loss of the power supply and the engine was unable to function. Failure of the fuse is discussed in more detail below.

- The jet unit water pump relied on the engine to drive the impeller and draw water through an intake under the hull and force it out through a pipe and steering nozzle mounted on the transom. This in turn provided the thrust and directional control of the jet boat.

- Immediately after the fuse failed the engine stopped and it was unable to drive the impeller. Without a supply of water, the jet unit stopped and was unable to provide the thrust required for steering, forward and reverse power, and braking.

- Consequently, the jet boat driver was unable to steer clear of any dangers or reduce the effect of any impact by slowing down or reversing. The Commission found that the actions of the jet boat driver were not contributory.

- The following section analyses the circumstances around why KJet 8’s engine stopped and control of the boat was lost.

Single point of failure

- When the 20 ampere fuse was replaced, the engine started and operated normally.

- To confirm that the failed fuse was the cause, and that there were no other contributory factors, the investigation examined other parts of the operating system that could potentially have prevented the engine from functioning correctly.

- A fuel supply failure was eliminated. The engine would not have stopped instantly, the low fuel indicator on the dashboard was not lit, there were no fuel leakages observed and the quality of the fuel was satisfactory.

- There was no evidence of a mechanical failure before or after the accident. When the engine was eventually restarted it ran satisfactorily without any repair or modification work being undertaken, other than replacing the failed fuse.

- About the complete electrical system, it was determined that the circuit from the battery to the point of fuel ignition was fully operational both before and after the accident. An electrical relay fitted in line with the failed 20 ampere fuse was tested and found to be operating satisfactorily.

- The Commission found that it is virtually certain the cause of the unexpected and instant engine stop, resulting in total loss of vessel control, was mechanical failure of the powertrain relay fuse as described in section 2.

- The mechanical failure of the fuse was very likely a result of a load being imparted onto the leg of the fuse from the wire of the engine wiring loom as shown in figure 13. That load was cyclic because it was also subject to engine vibrations.

Regulation

Safety Issue: The regulatory requirements for commercial jet boat operations do not fully mitigate the inherent risk of single point failure of the propulsion and control systems resulting in a total loss of control of the jet boat.

- Adapting readily available automobile engines for use in a marine environment is not uncommon. In the case of KJet 8 the Kodiac engine had been marinised by KEM in the USA. KEM conduct validation testing on their designs, which includes vibration endurance tests. They have also delivered thousands of marinised engines similar to the engine installed on KJet 8, which in turn have accumulated thousands of operational hours.

- There have been no known previous incidents recorded where the mechanical failure of a single fuse has resulted in loss of control. As a result, manufacturers, designers and builders have likely been oblivious to the potential problem.

- The rare nature of this fuse failure means it is unlikely it represents a systemic safety issue. However, given the mechanical failure of the fuse was attributed to the effects of vibration and the arrangement of the connecting wires (both of which were original design factors), over time similar incidents could potentially occur on any vessel where such an engine and fuse box is fitted.

- To prevent similar occurrences, operators should ensure that flexing of the wires at the back of the fuse connections cannot apply a mechanical load to the fuse connectors.

- A recommendation would have been made to KJet to ensure the safety of the fuse arrangement in their vessels. However, the Commission is satisfied that the safety action taken to date by the company has addressed the safety factors identified during the investigation (see section 5).

- On this occasion it was an unforeseen mechanical failure that caused the fuse to fail but equally, and by design, the fuse could have failed as a result of an electrical overload. The consequences for passenger safety would be exactly the same. Likewise, there are many other potential points of failure which could lead to immediate and total loss of control of the jet boat.

- It is therefore important to recognise that resolving the safety issue directly associated with the fuse arrangement does not in itself address the wider systemic issue of identifying single point failures on critical control systems. This accident occurred as a result of a single piece of equipment failing, and there was no redundancy in the operating system from which a recovery could be made.

- Identifying critical systems and single points of failure in a control system is a key risk mitigation requirement to ensure that a jet boat is “adequate for the nature of commercial jet boat operation” as required in Maritime Rules Part 82.

- This incident, and the incident at Skipper’s Canyon (TAIC inquiry MO-2019-201 Skippers Canyon), indicates a need for operators to improve passenger safety by proactively carrying out more thorough and detailed technical assessments by identifying both potential single point failures critical to the safe operation of individual vessels and the necessary mitigation measures.

- The process should be an integral part of meeting the Maritime Rule requirements for jet boats to be ”adequate for the nature of commercial jet boat operation”. To provide a reasonable level of reassurance that the process has been considered in-depth it should be fully documented in the operator’s SOP, made available for inspection by the regulator, and be inspected as part of the auditing process.

-

In 2019, as a result of the inquiry MO-2019-201, the Commission recommended to the Director of MNZ that:

…they ensure all operators working under Maritime Rules Part 82 have identified on each jet boat all systems that are critical to the safe operation of the boat, and to have a documented inspection and maintenance system in place that covers those critical systems and also ensures they meet manufacturers’ specifications. The inspection and maintenance system should complement rather than replace any existing system of daily checks. (010/19)

- MNZ have ongoing work on this, and to date have strengthened the governance of commercial jet boat compliance auditing, and also introduced an audit checklist as described in section 2. The Commission welcomes the progress already made by MNZ.

-

The KJet accident highlights the vulnerability of jet boats to single point failure and loss of control, and the need to identify and mitigate single points of failure for a jet boat’s control system. The Commission has therefore made a recommendation to the Director of MNZ that

They engage with operators working under Maritime Rules Part 82 to identify jet boat systems which carry the risk of single point failure that would result in a total loss of control of the jet boat, and discuss possible measures that could be taken to reduce the risk to passengers and crew to as low as reasonably practicable.

Driver incapacitation

- The driver was incapacitated and a passenger reported the accident using the boat’s radio. The ability of passengers to raise an alarm cannot always be guaranteed. In the event of a driver becoming incapacitated a system of alerting rescue services is required.

- Since the accident, KJet have installed an emergency button on all jet boats for passengers to use in the event the jet boat driver is incapacitated. The button triggers an alarm at the Marine Base to alert shoreside management of an issue with the jet boat. The pre-departure brief for passengers includes an introduction to the purpose, location and operation of the emergency button.

Findings Ngā kitenge

- The actions of the jet boat driver were not contributory.

- In the event of a driver becoming incapacitated a foolproof system of contacting rescue services is required.

- The fuse failure resulted in a loss of power to the jet boat’s propulsion and control system. As a result, there was an immediate and total loss of control of the jet boat.

- It is virtually certain that the single cause of the engine stopping was the mechanical failure of a 20 ampere fuse fitted inside the fuse box and mounted to the engine.

- Mechanical failure was very likely caused by a load being imparted onto the leg of the fuse by unsupported wiring, which was susceptible to resonating with engine vibrations back and forwards.

- Regulatory requirements for commercial jet boat operations do not fully mitigate the inherent risk of a single point failure of the propulsion and control systems.

- Had the fuse failed as a result of an electrical overload the consequences for passenger safety would be exactly the same as a mechanical failure.

- Operators can improve passenger safety by: proactively carrying out more thorough and detailed technical assessments; and identifying both potential single point failures critical to the safe operation of individual vessels and the necessary mitigation measures.

Safety issues and remedial action Ngā take haumanu me ngā mahi whakatika

General

- Safety issues are an output from the Commission’s analysis. They typically describe a system problem that has the potential to adversely affect future operations on a wide scale.

- Safety issues may be addressed by safety actions taken by a participant, otherwise the Commission may issue a recommendation to address the issue.

Safety Issue: The regulatory requirements for commercial jet boat operations do not fully mitigate the inherent risk of single point failure of the propulsion and control systems resulting in immediate and total loss of control of the jet boat.

-

On 12 December 2019, the Commission recommended to the Director of MNZ that:

…they ensure all operators working under Maritime Rules Part 82 have identified on each jet boat all systems that are critical to the safe operation of the boat, and to have a documented inspection and maintenance system in place that covers those critical systems and also ensures they meet manufacturers’ specifications. The inspection and maintenance system should complement rather than replace any existing system of daily checks. (010/19)

-

In response to recommendation 010/19 the Director of MNZ responded in part that they had taken the following safety actions to address this issue:

Maritime NZ is currently developing a programme to extend areas within an operation that are audited under Part 82 requirements. The audits will be covering a wide range of topics but will specifically cover two key items:

- The adequacy of the driver competency programmes required by the rule, and checking that they have been properly implemented by each operation.

-

The adequacy of the maintenance programmes required by the rule, and checking that they have been properly implemented by each operation.

As part of this programme of work Maritime NZ is also exploring working with commercial jet boat operators to develop critical systems maintenance guidance.

- The Commission welcomes the safety action to date about that recommendation. However, it believes more action needs to be taken to ensure the safety of future operations, specifically the need for operators to identify and document thorough assessments on critical systems and single points of failure, including the measures taken to reduce the risk to passengers and crew to as low as reasonably practicable. Therefore, the Commission has made a recommendation in section 6 to address this issue.

-

MNZ has taken further action since recommendation 010/19 was issued, as described below:

Since our response to Draft Report MO-2019-201 in December 2019, MNZ has undertaken a significant overhaul of the system for auditing SOPs under Part 82.

Previously, an MNZ-delegated third party was responsible for compliance activities under Part 82, including:

Inspecting all the vessels requiring an inspection;

Assessing jet boat driver’s license applicants; and

Auditing operator SOPs.

In 2020, the responsibility for auditing operator SOPs was transferred to MNZ staff, with third party delegation limited to vessel inspections and assessing some license applications. The criteria and processes for this limited delegation are still being finalised. Having MNZ staff responsible for auditing all operator SOPs allows for:

Certainty that audits are of high quality; and

Strong oversight of the operators as well as the performance of any delegated third parties.

Please see attached our Part 82 Audit Checklist (MSF293). As you can see, audits are in-depth and cover the adequacy of driver competency and maintenance programmes.

For your information, we are also working toward closing TAIC Rec. 010/19, the recommendation that came out of Report MO-2019-201, and hope to be in a position to do that soon.

Other safety actions

-

The following safety actions have been taken by KJet to address key safety factors identified during the investigation and therefore the Commission has not made a recommendation.

- Heavy Duty Fuses and Relays – The investigation into the cause of the engine shutting down identified the 20-amp fuse for the powertrain relay on the engine to be the fault. The fuse did not blow; but fractured internally creating an open circuit, resulting in the engine shutting down. The fuse/relay box is mounted directly onto the engine as supplied by Kodiak. The fuses and relays are of the micro style, so they have much smaller pins with a lot less contact into the receiver in the fuse box.

- After consultation with Kem equipment and with our auto electrician as to what the best way is to prevent this from happening again and looking at the options of remote mounting, redundancies etc, we decided to change from push in fuses to a bolt in style fuse, and to change from Micro Relays to standard size blade HD Bosch relays, and mount these all on vibration dampers on to the factory mount point.

- We are installing the above set up on all our Kodiak D.I. engines in the fleet. [a photo of the new arrangement is shown below – see figure 14]

- Centre Bars – We have designed and fabricated centre bars to protect both staff and customers should a boat come into contact with tree branches, they are designed to deflect branches and debris away from the occupants of the boat.

- This safety bar system is being installed through-out our fleet.

- Emergency Button – We have installed an emergency button specifically for passengers to use in case of an emergency if the driver has been incapacitated, this button when pushed activates an alarm located at the Operations Base which is monitored at all times.

- The Emergency Button is being installed through-out the fleet as well.

- We have replaced our safety signage both on board the boats and the safety boards used by the drivers to reflect the new emergency button

- In an instance when the Emergency Button is pushed, we would then log on to the onboard surveillance camera system from the Operations Base and get real time camera footage and the GPS location of the boat (official safety action response from KJet).

Recommendations Ngā tūtohutanga

General

- The Commission issues recommendations to address safety issues found in its investigations. Recommendations may be addressed to organisations or people, and can relate to safety issues found within an organisation or within the wider transport system that have the potential to contribute to future transport accidents and incidents.

- In the interests of transport safety, it is important that recommendations are implemented without delay to help prevent similar accidents or incidents occurring in the future.

New recommendations

-

On 27 April 2022, the Commission recommended to the Director of MNZ that they engage with operators working under Maritime Rules Part 82 to identify jet boat systems which carry the risk of single point failure that would result in a total loss of control of the jet boat, and discuss possible measures that could be taken to reduce the risk to passengers and crew to as low as reasonably practicable. (008/22)

On 5 May 2022, the Director of MNZ replied:

We accept this recommendation. In response, building on actions taken in response to recommendation 010/19 (as detailed in paragraph 5.6 of the draft report), we will empower Maritime NZ staff and delegated parties to engage on issues related to single point failure during systems audits, vessel inspections, and other routine engagement. Additionally, at this year’s New Zealand Commercial Jet Boating Association (NZCJBA) annual national conference, we will make sure that discussions include issues related to single points of failure. Finally, Maritime NZ is working with the NZCJBA to develop guidance to support operators to identify and reduce risks related to single point failure.

Key lessons Ngā akoranga matua

- When a boat is under the control of a single crew member it is imperative that in the event of them becoming incapacitated there is a system in place to alert rescue services.

- It is essential that operators have a robust process in place to identify critical systems and single points of failure that, if defective, can have significant impacts on the safety of the operation.

- While the Maritime Rules provide a minimum safety standard, operators are still responsible for identifying and mitigating risks and hazards specific to their own operations and should endeavour to use that process to improve their safety standards over and above the minimum required.

Conduct of the inquiry He tikanga rapunga

- On 21 March 2021, MNZ notified the Commission of a jet boat accident occurring on the Shotover River near Queenstown resulting in injuries to some of the persons on board. The Commission subsequently opened an inquiry under section 13(1) of the Transport Accident Investigation Commission Act 1990 and appointed an Investigator-in-Charge.

- On 22 March 2021, a protection order was put in place to protect evidence related to the jet boat.

- Also on 22 March 2021, three investigators travelled from Wellington to Queenstown to gather evidence. One returned on 25 March and the other two on 26 March.

- On 16 April 2021, Quest Integrity were engaged to assist with identifying the circumstances and causes of the accident.

- On 27 April 2021, one investigator and a representative from Quest Integrity travelled to Queenstown to inspect the jet boat and gather evidence and they returned on 28 April.

- On 22 February 2022, the Commission approved a draft report for circulation to six interested persons for their comment.

Glossary Kuputaka

- Marinisation

- Marinisation is the process of modifying or converting for marine use.

Data summary Whakarāpopoto raraunga

Details

Appendix 1. MNZ Commercial Jet Boat Operations River Audit Checklist

Related Recommendations

The Commission recommended to the Director of MNZ that they engage with operators working under Maritime Rules Part 82 to identify jet boat systems which carry the risk of single point failure that would result in a total loss of control of the jet boat, and discuss possible measures that could be taken to reduce the risk to passengers and crew to as low as reasonably practicable.