A fatal controlled flight into terrain occurred after aircraft turned away from planned/ authorised route in uncontrolled airspace. Terrain proximity awareness system either too dim or not selected. All pilots should follow Civil Aviation Rules, apply validation steps such as cross-checking altitude and distance for flight plans, use onboard safety equipment. Flight training schools should have robust flight authorisation systems.

Executive summary Tuhinga whakarāpopoto

What happened

- On 23 March 2019, a four-seat Diamond DA42 aeroplane was being flown from Palmerston North to Taupō as part of a navigation flight originating from Ardmore. Thirty minutes into the flight, while at 9,000 feet (2,745 metres) above sea level, the aeroplane was turned away from the planned track and the pilot made a ‘top of descent’ radio call to the flight information service. The aeroplane commenced a descent at that time.

- At 2213, about eight minutes after the descent had commenced, the aeroplane struck terrain at about 4,500 feet (1,371 metres) and about 38 kilometres south of Taupō Aerodrome. The pilot and safety pilot were fatally injured.

Why it happened

- The Transport Accident Investigation Commission (Commission) found that the pilot descended the aeroplane below the specified minimum safe altitude for the area in which the aeroplane was being flown, and a controlled flight into terrain occurred.

- The Commission found that the pilot operated the aeroplane outside the parameters required for ‘direct routing’ navigation in uncontrolled airspace, when attempting to connect with an instrument approach from the en-route phase of the flight.

- The Commission found no evidence that any malfunction of or unserviceability with the aeroplane, or any medical issue, contributed to the accident.

- The Commission found that the aeroplane was equipped with a terrain proximity awareness capability but that it was very likely not used by the pilot.

- The Commission found that weaknesses in the flight-authorisation procedures permitted pilots to conduct flights without the applicable authorisation, and therefore supervision, of senior instructors. This is what occurred in this case.

- The Commission found that the pilot was licensed and rated to conduct flights in accordance with instrument flight rules and at night. However, both the pilot and the safety pilot had little experience in navigating at night under instrument flight rules. They were therefore subject to an increased level of supervision by the operator until they gained more experience.

What we can learn

- The key lessons identified from the inquiry into this occurrence are:

- pilots, especially instructor pilots, should be fully aware of the parameters prescribed by the Civil Aviation Rules, including for navigating away from pre-planned and instrument flight rules- approved flight routes

- where possible, pilots should use and be proficient in the full capabilities of the flight instrumentation systems available to them. In this case, thorough training in the use of onboard ground-proximity conflict and warning systems, including the dimming of instrument and cockpit lights at night, would have enhanced situational awareness

- flight training schools should ensure that their procedures for flight authorisation and supervision are sufficiently robust to ensure that pilots can only conduct training flights after obtaining appropriate authorisation and supervision.

Who may benefit

- Pilots, instructor pilots and flight training schools may all benefit from the findings in this report.

Factual information Pārongo pono

Narrative

- On 23 March 2019 at 1940 (times are in New Zealand daylight time (co-ordinated universal time + 13 hours) and expressed in the 24 -hour format), a four-seat Diamond DA42 aeroplane, registration ZK-EAP (the aeroplane), owned and operated by Ardmore Flying School (the operator), departed Ardmore Aerodrome on an instrument flight rules (IFR) (Flight by reference to instruments. The alternative is flight by visual reference, termed visual flight rules) night navigation consolidation flight. On board were a pilot and a safety pilot. The planned route was from Ardmore to Palmerston North, returning via Taupō. The flight south to Palmerston North was uneventful.

- While on the ground at Palmerston North Aerodrome, the pilot talked to Ōhakea Control and obtained an air traffic control clearance for the next leg to Taupō (yhe Palmerston North air traffic control tower was off watch). The aeroplane was “cleared Taupō via [reporting points (sometimes termed waypoints. Reporting points can be compulsory or non-compulsory)] APITI, RUAHI, TURUA, TAIKI at 9,000 feet [2,745 metres (m)]” above sea level (all altitudes are in reference to above mean sea level) (see Figure 3) (approval is required for aircraft to operate in controlled airspace and is subject to the direction of the responsible controller). At 2135 the aeroplane departed Palmerston North. Once clear of Palmerston North Aerodrome the pilot called Ōhakea Control and advised climbing past 2,300 feet (700 m) for 9,000 feet. The Ōhakea controller acknowledged the call and advised that the aeroplane had been identified.

- At 2152 the Ōhakea controller passed on the latest weather information for Taupō. This was given as a surface wind of 030° magnetic at 8 knots (15 kilometres per hour [km/h]), 17 kilometres (km) visibility and overcast cloud at 4,500 feet (1,371 m). This was acknowledged by the pilot. Shortly afterwards, the Ōhakea controller instructed the pilot to change radio frequency to Christchurch Information as the aeroplane was leaving controlled airspace (in uncontrolled airspace around New Zealand, flight following is typically provided by Christchurch Information, operating on a range of frequencies. Pilots are responsible for maintaining their own separation from terrain and other aeroplanes) and flying into uncontrolled class G airspace (airspace internationally and in New Zealand can be either controlled or uncontrolled, and is further divided into various classes. Uncontrolled airspace is termed class G airspace).

- At 2203, after several attempts, the pilot established radio communication with Christchurch Information. The Christchurch flight information officer (FIO) (Airways New Zealand provides a flight information service through a flight information officer, who offers limited assistance for pilots operating in uncontrolled airspace. The pilots remain responsible for terrain-conflict avoidance and separation from other aircraft) advised that the aeroplane was in uncontrolled airspace and that there was no reported traffic at 9,000 feet to Taupō. The FIO also passed on the local Manawatū altimeter pressure setting (when the local pressure or QNH is set on an altimeter, it provides altitude above mean sea level) and requested the pilot call when they were commencing their descent. The pilot acknowledged the request.

- At 2205 the aeroplane was recorded on radar turning left as it passed TARUA. At the same time the pilot reported ‘top of descent’ and the aeroplane was recorded as starting to descend from 9,000 feet. The FIO replied, advising that there was no reported traffic for the descent to Taupō, and asked, “Which runway lights would you like?” (the aerodrome approach and runway lighting were remotely controlled by the FIO). At 2207, after two further calls by the FIO, the pilot responded and was given the local area altimeter pressure setting.

- At 2209 the pilot requested the lighting for runway 35 (runways are identified by their magnetic alignment, rounded to the nearest 10 ° increment. Runway 35 is therefore aligned about 350° magnetic) and confirmed that they would be conducting the “RNAV [area navigation] 35 approach” followed by the “missed approach (the phase of an instrument approach when an aircraft overshoots from the approach and climbs back to a safe altitude) onwards [to] Ardmore” (see Figure 9). The latest Taupō altimeter pressure setting was passed during this time. The pilot and the FIO confirmed the routing to Ardmore and when the air traffic control clearance for the next leg could be given. The last transmission by the pilot concluded at 2212:48.

- The wreckage of the aeroplane was located at about 1030 the following day. Both occupants had died in the accident.

Background

- The pilot, a Category B instructor with the operator, was working towards gaining a multi-engine instrument instructor endorsement. This was in accordance with the operator’s IFR instructor training programme approved under Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) exemption 15/EXE/20. The purpose of the flight was for the pilot to gain experience as the ‘pilot in command’ in a range of areas, including with multi-engine aeroplanes and flying cross-country under IFR and at night. This formed part of the operator’s CAA-approved instructor training programme, for the purpose of qualifying the pilot as a multi-engine IFR instructor.

Safety pilot

- The safety pilot was also a Category B instructor and was accompanying the pilot in accordance with the operator’s procedures for IFR training flights. Civil Aviation Rules Part 61 – Pilot Licences and Ratings, and Part 91 – General Operating and Flight Rules, both referred to the role of a safety pilot. A safety pilot was to have adequate visibility outside the aircraft, a current pilot’s licence and both aircraft type and instrument ratings. For simulated instrument flight (flight in simulated instrument meteorological conditions, with a pilot typically flying with a hood or cover over their head to prevent their looking outside the aeroplane), a safety pilot had to be able to take control of the aircraft. The safety pilot on the accident flight met the criteria to perform the function.

-

The operator’s standard operating procedures directed that “pilots will not be approved for single-pilot IFR, without a safety pilot, unless authorised by the HoT [head of training].” The procedures then described the role of the safety pilot as:

The safety pilot is essentially a passenger on the flight and as such is legally unable to touch the controls, or the radios. Once an instructor on board begins to give instruction they also become Pilot in Command so there is a fine line that needs to be navigated to ensure the students are getting the maximum out of the flight without making any errors relating to safety (note: failing to follow correct procedures also compromises safety).

- The procedures then listed the duties required of the safety pilot in relation to the “sort of errors that may require intervention from the safety pilot or not”. These included:

- write all clearances, and communicate errors with readbacks, understanding, or responsiveness

- point out to the pilot flying any altitude/speed/tracking deviations more than 100 [feet]/5 knots/half scale deflection respectively

- confirm with flying pilot their intentions if there is a likelihood of serious infringement of airspace/aircraft limits/IFR procedural limits

- keep a good lookout, listening watch, and high level of situational awareness, and identify to the pilot flying the position of any conflicting traffic

- communicate/discuss any issue at any time that may directly compromise the safe conduct of the flight – i.e. a decision to fly into bad weather etc.

- Any safety-critical intervention by the safety pilot had to be followed up with an incident report on completion of the flight.

The flight

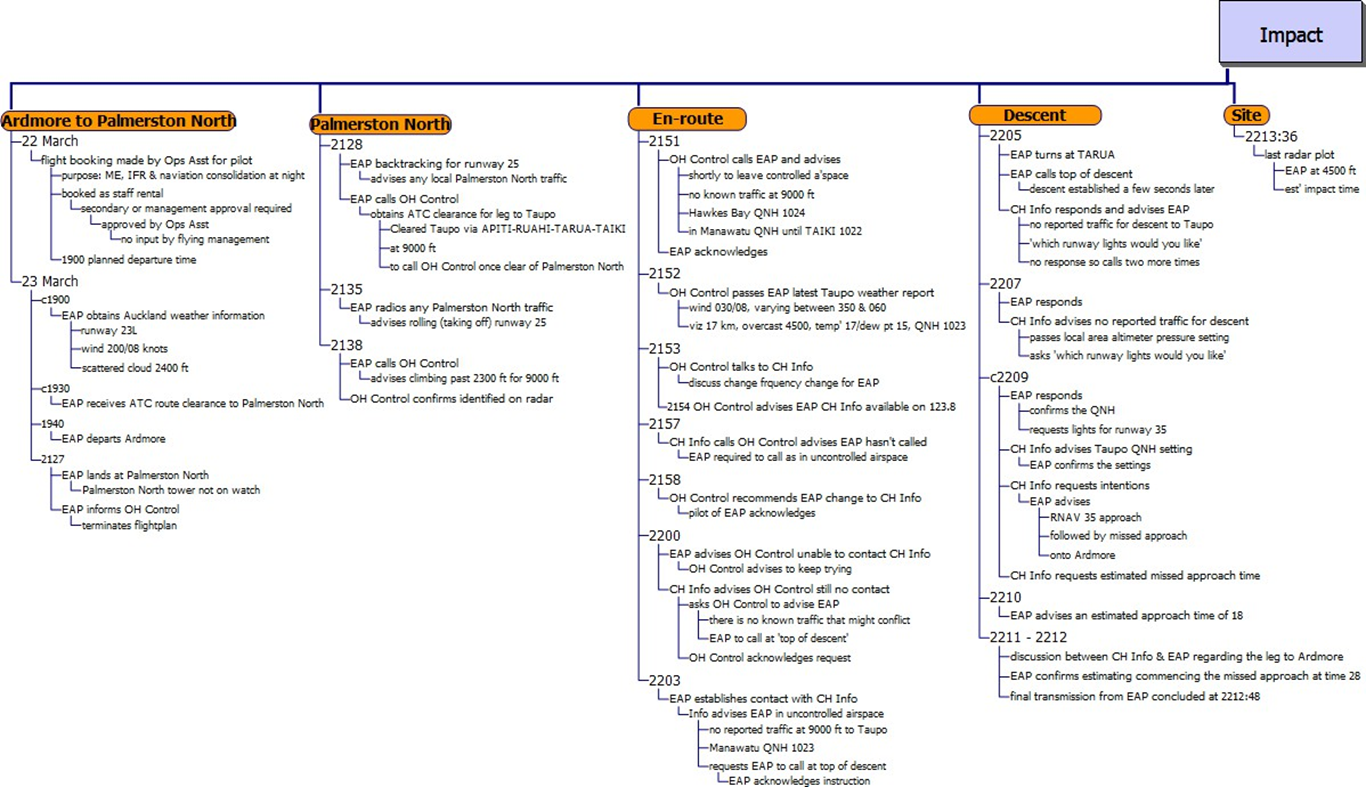

- The pilot booked the flight at 1132 the day before the accident, using the ‘staff rental’ (one of the options available for booking a flight) facility built into the operator’s electronic booking system. A timeline of significant events is at Appendix 1.

- The operator was required by the CAA to ensure that IFR flights undertaken by Category B instructors were authorised by training management (typically the IFR team leader or a Category A instructor). On the day of the accident, a Saturday, one of the operator’s Category A instructors was present but left work that evening after completing a navigation training flight. Because of other continued flying activities, the operator’s operations or duty desk remained staffed by a senior Category B instructor as required by the operator’s procedures.

- The pilot and safety pilot arrived at the operator’s offices after the Category A instructor had left. The pilot then accessed the authorisation system and was recorded as self-authorising the flight at 1754. The operator’s flight booking form showed the pilot nominated a ‘due back’ time of 0030 the next day.

- The pilot also submitted an IFR flight plan to Air Traffic Services (ATS) for all three of the flight sectors from Ardmore to Palmerston North and return. The flight plan included a proposed take-off time from Ardmore of 1930 for the flight to Palmerston North. The return flight to Ardmore was to be via Taupō and was planned for a take-off from Palmerston North at 2140 and an arrival at Taupō 45 minutes later. The planned route from Palmerston North to Taupō was via reporting points APITI, RUAHI, TARUA and TAIKI at an altitude of 9,000 feet. This would result in the aeroplane approaching Taupō Aerodrome from an easterly direction. The return time at Ardmore was planned to be 2330 (this was earlier than the booking time return of 0030, which allowed for potential delays along the way).

- At about 1900 the duty instructor (the job title used the term ‘operations assistant’) noticed that the pilot and safety pilot were preparing for their flight. The duty instructor, familiar with the latest weather reports and aware of occasional showers in the area, thought the forecast “didn’t look the best” for the planned flight. This was brought to the attention of the pilot. The pilot reportedly checked the weather information again and said to the duty instructor that they were happy with it. The duty instructor, as a Category B instructor, was able to supervise Category C instructors and students only and was therefore not able to authorise the pilot’s flight in accordance with the operator’s procedures.

- Airways New Zealand surveillance data recorded the aeroplane taking off from Ardmore at 1940 and landing at Palmerston North at 2127. The aeroplane then took off from Palmerston North at 2135 for the return flight to Ardmore via Taupō. The landing and take-off at Palmerston North were on runway 25.

- The surveillance data showed that at 2205, while in the cruise at 9,000 feet on a north-easterly flightpath at TARUA, the aeroplane turned onto a north-westerly flightpath. This change in flightpath was coincident with the pilot making a radio call to the FIO stating “top of descent”.

- The data showed that shortly after the radio call the aeroplane started to descend steadily at 500 feet (152 m) per minute, and after six minutes the rate of descent increased to 750 feet (228 m) per minute.

- Between 2207 and 2212, the FIO and the pilot discussed the type of instrument approach to be flown, the runway lighting and the onwards clearance to Ardmore after the planned missed approach. There were no further routine or emergency radio transmissions heard from the aeroplane. (See paragraphs 2.44 to 2.46 for a further discussion on post-accident events.)

Personnel information

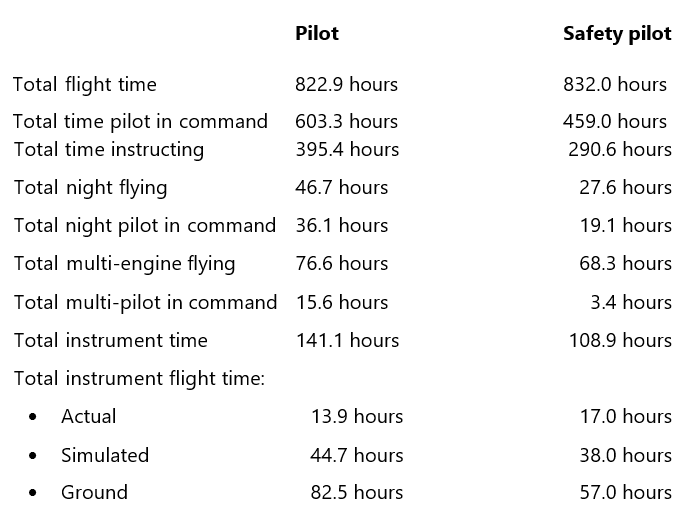

- Both the pilot and the safety pilot held aeroplane commercial pilot licences, Category B flight instructor ratings, multi-engine instrument ratings and current medical certificates, and were employed by the operator as flight instructors. The pilot commenced flying training in September 2011 and obtained the Category B instructor rating on 31 May 2018. The safety pilot commenced flying training in June 2009 and obtained the Category B instructor rating on 15 February 2019.

- The pilots had logged the following flight hours:

At the commencement of the flight the pilot had completed 8.8 hours of the required 25 hours of IFR cross-country flying.

- The most recent medical certificate issued to the pilot by the CAA was dated 10 January 2019. The certificate precluded the pilot from carrying passengers on “single pilot air operations”. This related to commercial flights and was therefore not applicable to the pilot flying with students, non-fare-paying passengers or the safety pilot. The certificate therefore was valid at the time of the accident.

Aircraft information

- The aeroplane was a Diamond Aircraft Industries DA42 Twin Star, serial number 42.258, manufactured in Austria in 2007. The aeroplane was powered by twin inline four-cylinder, turbocharged Centurion 2.0 TAE 125-02-99 diesel engines, manufactured by Thielert Aircraft Engines. The engines were fitted with three-blade constant speed propellers.

- The aeroplane had first been operated in Australia with the registration VH-DTS. It had then been imported to New Zealand in August 2018 and registered as ZK-EAP.

- The aeroplane was mainly constructed of carbon-composite material and each engine was controlled by a full authority digital engine control (FADEC) system.

- The aeroplane was equipped with a Garmin G1000 integrated flight instrument system and a three-axis GFC 700 digital autopilot. The G1000 system in the accident aircraft comprised two electronic display units. The display unit on the left was typically used as the primary flight display. The display unit on the right was typically used as a multifunctional display (MFD) (see Figure 4). The MFD could be used to programme flight plan data and display engine parameters and navigation information, including a moving map and terrain-conflict-proximity information. The functions could be moved between the two display units.

- Terrain-conflict-proximity information was displayed graphically on the moving map. Colour-coded areas of the map corresponded to the altitude of the aeroplane determined by the global positioning system (GPS) with respect to the terrain elevation stored in the digital database loaded into the G1000 system.

- Yellow on the map signified that the terrain elevation was within 1,000 feet (304 m) of the aeroplane’s GPS altitude. Red signified that the terrain elevation was within 100 feet (30 m) of the aeroplane’s GPS altitude (see Figure 5). The terrain conflict proximity functionality could be selected on and off by the pilot. In night or low-light flight the displays could be dimmed to reduce the glare generated by the display units.

- The G1000 system manufacturer offered an optional augmentation to the terrain-conflict-proximity functionality. The augmentation consisted of a secure digital card (Secure Digital, officially abbreviated to SD, is a proprietary non-volatile memory card format developed by the SD Association for use in portable devices) that unlocked the Class-B Terrain Avoidance and Warning System (a system that provides flight crew with sufficient information and alerting to detect a potentially hazardous-terrain situation, so the flight crew may take effective action to prevent a collision with terrain). The operator had not purchased this augmentation for its DA42 aeroplane fleet.

Meteorological information

- The graphical aviation forecast (GRAFOR) valid for approximately three hours prior to the time of the accident (see Figure 6) specified for the Bay of Plenty and Taupō area broken cloud (cloud is measured in eighths or oktas. Broken cloud is 5 -7 oktas) between 2,000-3,000 feet (609-914 m) and 6,000-8,000 feet (1,828-2,438 m), isolated embedded towering cumulonimbus above 2,000 feet, 20 km visibility with showers and rain and 5 km visibility with showers and rain in towering cumulonimbus cloud.

The GRAFOR valid for approximately three hours after the time of the accident (see Figure 7) detailed broken cloud between 1,500-2,500 feet (457-762 m) and 6,000-9,000 feet (1,828-2,745 m), isolated embedded towering cumulonimbus above 2,000 feet (609 m), visibility 20 km with showers and rain and 5 km visibility with showers and rain in towering cumulonimbus cloud, with cloud bases lowering to 800 feet (243 m).

- A rescue helicopter pilot from Taupō Aerodrome who attempted to search for the aeroplane at about midnight, said they had had to return to base as the conditions about the Kaimanawa Range had deteriorated and were not suitable for flying in visual meteorological conditions (flight under visual flight rules requires pilots to remain clear of cloud and in sight of ground or water).

- The cloud conditions in the Taupō region and around the Kaimanawa Range were forecast to worsen throughout the evening.

Recorded data

- The Transport Accident Investigation Commission (Commission) obtained ATS secondary surveillance radar data (primary radar transmits a radar pulse and is reliant on the detection of sufficient reflected energy. Secondary radar uses an aircraft’s transponder, which responds to a pulse from a ground-based antenna by transmitting a return signal. The return signal may include aircraft identification (transponder code) and altitude information). This data showed positional information such as latitude, longitude and altitude for the aeroplane during the accident flight. The data included the descent path of the aeroplane, with the final radar plot closely matching the actual location of the accident.

Site and wreckage information

- The accident scene was situated at 4,500 feet (1,371 m) on sloping ground in the Kaimanawa Range, approximately 38 km south of Taupō Aerodrome (see Figure 2).

- The aeroplane had first hit the ground with the left wing tip. The left wing had separated as a result. With the terrain sloping away, the remainder of the aeroplane had continued in the general direction of the original flightpath for a further approximately 250 m before striking the northern face of a gulley. The initial ground scar made by the left wing tip and the location of the wreckage showed that the aeroplane had been in about a straight and level attitude when the ground strike occurred (see Figure 8).

- The blades on the left and right propellers had shattered, and shards of wood had been dispersed widely throughout the first 100 m of the accident scene. The main portion of the aeroplane comprising the fuselage, right wing and right engine indicated the end of the wreckage trail. The right engine had separated structurally from the wing but remained attached to the wing by electrical cables. The left engine was found embedded in the ground nearby. There was no evidence of a fire having occurred.

- The aeroplane was examined at the accident scene and all flight-critical and major components were accounted for. The aeroplane was then removed and taken to the Commission’s facility, where a more detailed examination was conducted.

- The digital engine control units were removed from the aeroplane and sent to Bundesstelle für Flugunfalluntersuchung (the German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation) (BFU) for analysis of the recorded data. It was determined from the analysis of the data that the engines had been operating normally throughout the flight.

- There was no evidence found of any technical abnormality with the aeroplane or its engines that could have contributed to the accident.

Medical and pathological information

- Post-mortem examinations of the pilot and safety pilot identified nothing that might have been considered contributory to the accident. Toxicology results for both pilots were negative for any performance-impairing substances. Low levels of a medication were found in the pilot, but these were considered by a specialist aviation medical practitioner to be of such low value that they would not have impaired pilot’s performance.

Survival aspects

- Following the scheduled missed-approach time when the pilot was expected to call Christchurch Information to obtain the onwards clearance to Ardmore, the FIO called the aeroplane repeatedly. The FIO received no response so the aeroplane was declared overdue. The Rescue Coordination Centre New Zealand was informed and at 2245 initiated search action. Inclement weather prevented rescuers accessing the search area during the remainder of the night. A helicopter crew involved in the search eventually located the wreckage of the aeroplane at about 1030 the next day.

- The aeroplane was fitted with a 406-megahertz emergency locator transmitter (ELT), which did not emit an emergency locating signal as intended. Searchers were therefore reliant on available radar data and visual search techniques.

- The Commission has investigated previous accidents where ELTs failed to operate as designed. Following an accident in 2011 the Commission made two recommendations to the CAA on the matter (Inquiry 11-003: Inflight break-up ZK-HMU, Robinson R22, near Mount Aspiring, 27 April 2011).The issue was also added to the Commission’s Watchlist, under the title ‘Technologies to track and to locate’ and included rail and maritime transport as well as air.

Organisational information

- The operator of the aeroplane was a flight training school certificated under Civil Aviation Rules Part 141 – Aviation Training Organisations Certification. At the time of the accident the operator offered training for qualifications ranging from ab-initio private pilot to Category C commercial multi-engine IFR instructor (see www.aviation.govt.nz/assets/rules/consolidations/Part_061_Consolidation.pdf for information). At the time of the accident there were approximately 35 instructors and 150 students at the school.

- The operator employed Category C instructors on a salaried full-time basis, while also providing developmental flight training for them through the operator’s internal instructor training programme.

- The instructors were mentored through their training to Category B qualifications, after which they had more responsibilities in their roles and associated rises in salaries. The intent of this arrangement was to encourage instructors to remain with the operator until they ultimately left to further their careers with airlines.

- The pilot of the accident aeroplane, as part of the bonding agreement for salaried instructors, had been permitted ‘free gratis’ use of the operator’s aeroplanes for training purposes. The cost of the flying was held against a bond.

- Civil Aviation Rules 61.307(c) – Currency Requirements states that the holder of a Category A, B, C or D flight instructor rating must not give IFR cross-country navigation instruction unless the flight instructor holds a current instrument rating. The instructor must also have completed a minimum of 50 hours as ‘pilot in command’ on IFR cross-country operations that has been certified by a flight examiner in the instructor’s logbook.

- The CAA had granted the operator an exemption (15/EXE/20) from Civil Aviation Rules 61.307(c) for the training of instructors. This allowed a trainee instructor to conduct their accumulation of flight hours and IFR training under supervision with less than the minimum 50 hours as ‘pilot in command’ of a cross-country flight under IFR.

- The exemption allowed a reduced-hour programme for an upgrade to a multi-engine/ instrument instructor qualification, which involved a trainee instructor completing 25 hours’ instrument time/cross-country instead of the 50 hours. The reduced-hour programme called for seven hours of flight-simulator time and three hours of single-engine time, then 15 hours of instructor consolidation flight time. This was the purpose of the accident flight.

- The operator’s exposition stated that instructors seeking to take advantage of this programme had to agree to the initial 25 hours being strictly supervised by the HoT, the IFR Team Leader or a senior instrument-rated instructor approved by the HoT. Before undertaking a flight under the programme, instructors were required to obtain authorisation from a training management instructor. The pilot on the accident flight did not conform with this requirement before departing Ardmore.

Other relevant information

- The pilot, by deviating from the planned route at TARUA and flying directly towards MASKU, was flying an unevaluated route, termed direct routing (when an aircraft is flown along a route that has not been charted and has not been evaluated Sometimes referred to as ‘random routing’. AIP New Zealand, ENR 1.6-19, effective 6 February 2014). The following Civil Aviation Rules Part 19.217 – Transition Rules prescribes the standard for IFR flight on unevaluated routes:

CAR 19.217: Flight on unevaluated routes

a) Subject to paragraph (b), a pilot-in-command of an aircraft operating within the New Zealand flight information region under IFR using GPS equipment as a primary means navigation system is permitted random flight routing if operating—

1) within the area of a circle 20 nm radius centred on 43O36’S 170O 09’E (Mount Cook), at or above flight level 160; or

2) in any other airspace, at or above flight level 150.

b) A pilot-in-command of an aircraft is only permitted random flight routing within controlled airspace if authorised by ATC [air traffic control].

c) A pilot-in-command of an aircraft operating under IFR using GPS equipment as a primary means navigation system is permitted random flight routing below flight level 150 if—

1) authorised by ATC; and

2) ATC continuously radar monitor the flight for adequate terrain clearance.

- The following relevant excerpts from the Aeronautical Information Publication New Zealand outlines the authorisation for clearance to descend on an instrument approach provided for by a flight plan filed with ATS:

AIP [Aeronautical Information Publication] ENR 1.5: 4.4 Minimum Initial Approach Altitude

4.4.1 A clearance for an IFR aircraft to carry out an instrument approach:

a) except where otherwise instructed, authorises the aircraft to descend to the minimum procedure commencement altitude in accordance with:

i. STAR[standard instrument arrival];

ii. RNAV arrival;

iii. Route MSAs [minimum safe altitudes] including distance steps;

iv. 25 NM MSA sector altitude chart;

v. TAA [terminal arrival altitude] (a terminal arrival altitude provides a transition from an en-route structure to an RNAV approach procedure);

vi. VORSEC [VOR/DME Minimum Sector Altitude] chart; and

b) may include level restrictions applicable prior to approach commencement; and

c) may include level restrictions associated with circuit integration.

4.4.2 Except when under radar control, or in accordance with a specific arrival procedure promulgated in AD 2, the minimum initial approach altitude issued to an aircraft that is to carry out an instrument approach must be the higher of:

a) the minimum procedure commencement altitude shown on the instrument approach chart; or

b) the MSA for the route sector.

The MSA for the route sector will be determined using one of the following procedures. Where more than one option is available the procedure that offers the lowest MSA will be used.

i. the MSA for the ATS route including enroute descent (Distance) steps;

ii. the MSA after VORSEC chart steps;

iii. the altitude quoted in the 25 NM MNM Sector Altitude diagram;

iv. for GNSS [global navigation system satellite] approved aircraft the altitude quoted in the Terminal Arrival Altitude diagram.

Document downloads

Analysis Tātaritanga

Introduction

- The flight was a pre-planned IFR navigation exercise for the pilot to build flying hours towards a multi-engine instrument instructor qualification. Both the pilot and the safety pilot were appropriately qualified to conduct such a flight. The flight proceeded normally until the aeroplane deviated from the planned and evaluated route at TARUA directly towards MASKU. A descent from the cruise altitude of 9,000 feet (2,745 m) was commenced at this time. The aeroplane consequently descended below the minimum safe altitude (MSA) (the minimum safe altitude (MSA) is the lowest altitude which may be used which will provide a minimum clearance of 1,000 feet (304 m) above all objects located in the area contained within a sector of a circle of 46 km (25 nautical miles) radius centred on a radio aid to navigation (ICAO)) of 7,800 feet (2,377 m) for that sector. The aeroplane struck the terrain at about 4,500 feet (1,371 m) in about a straight and level attitude, and both pilots died in the accident.

- The investigation found no evidence of any medical or mechanical issues that may have contributed to the accident. The investigation found no evidence that either pilot was likely fatigued during the flight. The nature of the accident therefore has the characteristics of a ‘controlled flight into terrain’ accident. A controlled flight into terrain can be described as when “an airworthy aircraft under the complete control of the pilot is inadvertently flown into terrain, water, or an obstacle. The pilots are generally unaware of the danger until it is too late” (sources: ICAO [the International Civil Aviation Organization] and SKYbrary (SKYbrary is a repository of aviation safety information created by ICAO, the European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation and the Flight Safety Foundation)).

- The following sections analyse the circumstances surrounding the event to identify those factors that increased the likelihood of the event occurring or increased the severity of its outcome. It also examines any safety issues that have the potential to adversely affect future operations.

Flight authorisation and flight planning

Authorisation

- The operator’s reduced-hour instructor training programme syllabus specified that IFR cross-country flights had to be authorised by a training management instructor. The intent of this requirement was to provide an added level of supervision for pilots who were newly qualified and gaining experience in this type of flying.

- The operator’s computerised flight-booking system was designed to ensure that the syllabus for the course-based flights was completed in the correct order and that the appropriate authorisations were completed. The computerised system was not configured to limit personnel authorising their own flights electronically if the flight bookings were being made as ‘refreshers or rentals’. These bookings were made using the booking computer programme ‘tab’ to select the ‘refresher or rental’ booking page.

- The accident flight was planned for a weekend evening. The operator had minimal senior personnel available at this time. This was reported to be normal for that time of day and week. The flying schedule component of the operator’s computerised flight-authorisation system showed that the pilot authorised the flight at 1754 on the day of the accident as a ‘refresher or rental’.

- The pilot was well respected by fellow staff and known to be knowledgeable and conscientious. The pilot was very likely (‘very likely’ suggests a >90% probability. Refer to the verbal probability expressions) aware of the authorisation requirements, their having previously followed the correct process. Why the pilot elected to self-authorise the flight could not be determined. In the absence of the Category A instructor who had left earlier, the pilot could have phoned another senior instructor to approve the flight. Telephone records showed that this did not occur.

- A review of the operator’s flight-authorisation records found no previous incidence of unapproved flight self-authorisation by the pilot or any other instructor.

- The role of the duty instructor or operations assistant was to ensure the smooth-running of the flying schedule for the day. It was not to authorise flights, which was the role of a student’s allocated instructor. The duty instructor on duty on the day of the accident was being proactive in ensuring the pilot was aware of the current and forecast weather conditions.

- As a junior B-category instructor, and therefore less familiar with IFR navigation requirements, the duty instructor considered the pilot knew best.

- The operator advised that the Palmerston North to Taupō route flown by the pilot was not one of the approved routes typically used for single-pilot IFR training. This was because of the high MSA for the route, which a light twin-engine aeroplane such as the DA42 aeroplane would struggle to maintain should an engine malfunction occur. Any flight to Taupō would normally have approached from the north or west where there were lower MSAs available.

- Following the accident the operator advised that had a senior instructor examined the proposed flight plan and weather information as part of the authorisation process, the flight would most likely not have been authorised. Following the accident, the operator’s standard operating procedures were amended to state that the chief flying instructor’s approval was required for any single-pilot IFR navigation flights other than those routes specifically listed in the procedures. (Note the Commission would also expect that, before authorising such a flight, an authorising person would review how a pilot intended to transition from the intended route to an instrument approach. See the section below on ‘Diversion from planned track and descent through the sector minimum safe altitude’.)

- Further, the operator amended the list of tasks for duty instructors to include, among other things, ensuring that no flight (including simulator flight) takes place without the correct authorisation, and informing the operator’s chief flying instructor should any student or instructor fail to follow procedures.

Flight planning

-

A pre-planned pilot’s flight log was found at the accident scene. This listed the planned track reporting points from Palmerston North to Taupō. The entries are depicted in the following table:

- The flight log showed that the pilot had reviewed and validated each of the legs along the planned route, including the relevant MSAs. The flight log made no reference to the deviation from the planned track at TARUA. Therefore, it would appear that the pilot did not undertake any form of route check or validation of the revised route from TARUA, or at the very least did not record it.

Diversion from planned track and descent through the sector minimum safe altitude

The diversion

- At 2205, while near TARUA, 46 nautical miles (85 km) south of Taupō, flying at a groundspeed of 165 knots (305 km/h) at 9,000 feet, on a track of 003° magnetic, the pilot advised the FIO that the aeroplane was at ‘top of descent’. The ATS surveillance data showed that the aeroplane then turned left some 35° and started to descend. The rate of descent soon stabilised at 500 feet per minute.

- The turn was considered to be deliberate given the accuracy of the navigation up to TARUA, the large change in heading and the sustained new direction. However, despite ensuing radio communication between the pilot and the FIO, the pilot made no reference to the manoeuvre or to amending the flight plan with ATS.

- The reason for the change in flightpath could not be fully established; however, it was very likely influenced by the weather, both current and forecast. The weather report passed by the Ōhakea controller at 2152 was the first confirmation of the actual weather conditions at Taupō since the aeroplane had left Ardmore. Up until this time the pilot would not have been sure of which runway was in use at Taupō – runway 35 or runway 17.

- The wind at Palmerston North during the approach to land there was reported as 150° magnetic at less than 5 knots (9 km/h). The pilot subsequently landed and took off using runway 25. Both the wind and runway 25 at Palmerston North were closer aligned to using runway 17 at Taupō. With this new information, the pilot would have been able to determine the preferred instrument approach to fly.

- The pilot’s intention was confirmed when the pilot advised the FIO of the runway lights that should be turned on and that they intended to complete the RNAV 35 instrument approach and missed approach procedures. The new track from TARUA would take the aeroplane directly towards reporting point MASKU, which was one of three initial approach fixes that led to the RNAV 35 instrument approach (see Figure 9). The other two initial approach fixes, EMSAR and AKABA, catered for aircraft joining from a more northerly or western approach direction.

- The new routing from TARUA to MASKU also provided several advantages over the original route via TAIKI. Firstly, it was better orientated for the RNAV 35 approach. Secondly, it did not require the pilot to fly overhead Taupō and then head south before turning back to intercept the inbound track from reporting point AP506. And thirdly, because it was a shorter route, it offered a not-insignificant timing saving. The forecast deterioration in weather conditions during the late evening would also have had an influence.

Direct routing

- The change in route from TARUA took the aeroplane away from an evaluated and charted route. The aeroplane was now flying along a direct and unevaluated track in uncontrolled airspace below flight-level 150 or 15,000 feet. This did not meet the requirements of Civil Aviation Rules relating to IFR flight in uncontrolled airspace (see 2.56).

- To change the flight plan loaded in the aeroplane’s flight-navigation system while en route, the pilot would have had to update the route and activate it manually. This would have required a purposeful action from the pilot. Having updated the flight plan, the pilot should then have updated the flight log with the revised reporting points, and validated the integrity and safety of the new plan prior to activation. Once the plan was activated, the pilot could then have manually followed the new plan or used the autopilot function.

- The accuracy with which the aeroplane followed the route, including the altitude, from Palmerston North to TARUA and then turning directly overhead TARUA, made it likely that the aeroplane was being flown using the autopilot. In this situation, it would be expected that a pilot activating a revised flight plan would complete a validation of the new plan and update the flight log, and then monitor the aeroplane’s performance once the autopilot system was engaged into the appropriate mode. The validation of the revised flight plan would include safety checks, including whether the revised profile would complied with airspace restrictions, such as the MSA.

- To comply with Civil Aviation Rules, the pilot needed to continue flying the aeroplane along an evaluated route until it was within the 25-nautical-mile (46 km) terminal arrival altitude of an initial approach fix, then adhere to the relevant sector MSA until established on the instrument approach. Direct routing is only permitted in controlled airspace subject to obtaining clearance from air traffic control.

Minimum safe altitudes

- The MSA for the sector between TARUA and MASKU, specified in the Aeronautical Information Publication chart for the RWY 35 RNAV approach at Taupō Aerodrome, was 7,800 feet (2,377 m). After MASKU this lowered to 4,500 feet (1,371 m) until the initial fix AP506. This was the commencement point for the instrument approach. The surveillance data showed that at 2208, five minutes prior to the accident, the aeroplane descended below 7,800 feet. This was some 20 nautical miles (37 km) short of MASKU (see Figures 10 and 11).

- The rate of descent during the early part was steady at 500 feet (152 m) per minute. This would indicate that positive control of the aeroplane was being maintained. During the descent the pilot was engaged in regular radio communication with the FIO. There was no declaration of an emergency or a state of urgency (a condition concerning the safety of an aircraft or other vehicle, or of some person on board or within sight, but that does not require immediate assistance. Urgency messages should be preceded by the word ‘PAN’ repeated three times). The radio calls were what would have been expected in the circumstances – a planned descent for an instrument approach in uncontrolled airspace.

- At 2211, while at an altitude of 6,550 feet (1,996 m) and a groundspeed of 160 knots (296 km/h), the rate of descent increased to 750 feet (228 m) per minute and the groundspeed began to decrease slightly. This rate of descent continued for a further approximately two minutes until the aeroplane was approaching the terrain at about 150 knots (278 km/h). The increase in rate of descent was likely related to the pilot attempting to be at 4,500 feet and starting to configure (slowing an aeroplane to lower flaps and landing gear) the aeroplane by MASKU. The aeroplane struck the terrain at 4,500 feet in about a level attitude.

- The aeroplane descending below 7,800 feet, the sector MSA, indicates that an effective validation of the new route was not performed by either pilot. Had this been done, it should have revealed the likelihood of a conflict with the MSA and possibly a terrain conflict. It is therefore very likely that the pilots were focused on the commencement of the instrument approach and not what was immediately in front of and below them.

- If the MFD had been appropriately configured, and according to the G1000 reference guide for the DA42 aeroplane, it should have been depicting yellow terrain in proximity to the aeroplane for approximately one minute prior to the impact, and red terrain forward of the aircraft for approximately 20 seconds ( Figure 5). The red terrain corresponded to the ridgeline with which the aeroplane collided.

- The two alerts should have provided sufficient time for the pilots to initiate an immediate climb back to above the MSA. That this did not occur indicates four possibilities: the terrain proximity function was not selected; it was selected but the displays were dimmed to the extent that any alert was not clearly visible; the pilots did not react to the alerts; or there was an electronic display malfunction. It was considered exceptionally unlikely that either pilot would have ignored an altitude alert or that there was an electronic display malfunction for the following reasons:

- both pilots had learned to fly and subsequently instructed on single-engine aeroplanes equipped with G1000s, and therefore should have been familiar with the electronic displays and their functions

- the terrain proximity display was large, imposing and directly in front of the pilots

- there was no previously reported problem with the electronic displays fitted to the aeroplane, including during the flight immediately preceding this one

- a malfunction, including a partial malfunction, that relates to the display of navigation data on an MFD should be quickly detected by a pilot, especially when it is providing critical information

- should an MFD fail, the navigation information could still be displayed on the second electronic display

- should a double electronic display failure occur, the aeroplane was fitted with backup primary flight instruments (attitude indicator, altimeter, airspeed indicator and compass) that would have guided a pilot to climb to above the MSA

- the last radio transmission from the aeroplane was less than one minute before the collision, and this suggested nothing was wrong.

- It is therefore very likely that the terrain proximity was either not selected or, to assist with the pilots’ night vision, the display had been dimmed too far. The pilot and safety pilot subsequently focused on the task of descending at the required rate to achieve the promulgated terminal arrival altitude of 4,500 feet, prior to reaching MASKU. This would have assisted in a successful capture of the instrument approach for runway 35.

- When considering the forecast weather conditions and the weather reports from the searching helicopter pilots, it was very likely that the aeroplane was descending in cloud from 6,000 feet (1,828 m) to the point of collision with the terrain. The pilots therefore would have not been able to visually assess the proximity of the aeroplane to the terrain. The darkness further compounded the situation.

- Other than the graphical presentation of terrain proximity on the MFD, the aeroplane was not equipped with an impending-terrain-collision warning, nor was it required to be.

Minimum safe altitude warning

- As ZK-EAP descended below the 7,800-foot MSA for that sector, it was being recorded on radar. A radar display was available at the FIO’s workstation. However, while an FIO may refer to the display, an aircraft cannot be controlled in class G airspace because of the rules relating to this classification of airspace. Further, radar coverage in class G airspace is not always reliable and is often non-existent. Importantly, FIOs are not trained radar controllers, and air traffic surveillance procedures do not require FIOs to continuously monitor individual aircraft in uncontrolled airspace using radar. For this and other reasons described below, several of the functions available at some of the radar controllers’ workstations are not available or are disabled for an FIO. These include minimum safe altitude warnings (MSAWs), short-term conflict alerts and airspace intrusion warnings.

- A MSAW is a ground-based safety net designed to detect an aircraft descending too low, increasing the risk of a controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) accident. MSAW was designed specifically to protect an aircraft when it descended below the minimum safe altitude for an area while following an approved instrument approach procedure to a controlled aerodrome.

- A MSAW is restricted to controlled airspace, where an air traffic controller trained in the use of MSAW can react appropriately. The automated system generates an alert on the controller’s radar display in sufficient time to enable the controller to issue an instruction or warning to a pilot of an aircraft under their control. To ensure a MSAW is credible, the system requires reliable radar coverage, the transmission of aircraft altitude information and an accurate survey of the local terrain. The pilot and controller must also be on the same radio frequency.

- In New Zealand, MSAWs are only enabled for the instrument approaches (control zones and areas) at nine aerodromes where aircraft are under control of and radar monitored by air traffic controllers (for example, at Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch airports) (Refer Aeronautical Information Publication New Zealand (AIP) En-route 1.6 Radar Service and Procedures, paragraph 5.12.15, effective 5 February 2015). MSAWs are not available at other aerodromes where air traffic control is present (for example, at Napier, Nelson and Dunedin airports). It is also not available in uncontrolled class G airspace, including Taupō and the area where the accident occurred.

- An FIO, as part of the Area Flight Information Service for Airways New Zealand, works within the airways transportation system section. This section includes the national briefing office, the NOTAM (NOTAMS, or Notices to Airmen, are safety notices that may affect the conduct of a flight. Examples include runway work and obstructions at an aerodrome, activation of danger or restricted areas and military exercises) office and air traffic services supervision. These facilities are individually staffed during a normal working day and provide services such as aircraft flight plan processing, pre-flight planning information, aviation safety notices, weather information, departure and arrival coordination at busy aerodromes (defined as CAM or Collaborative Arrival Management) and alerting services. Up to five staff are required during a normal day. At night this reduces to one person responsible for all the functions. Radio communications for an FIO are therefore the primary, and in some cases the only, means of supporting a pilot tuned in to their frequency.

Other relevant CFIT accidents

- On 2 February 2005, Piper PA34 Seneca ZK-FMW was on an instrument approach to Taupō when it struck Mt Tauhara, 8 km north-east of the aerodrome. The Commission report described the accident as a CFIT accident and recommended to the CAA that onboard terrain awareness warning systems be fitted as standard equipment for Civil Aviation Rules Part 135 – Air Operations – Helicopters and Small Aeroplanes operators (Aviation Occurrence Report 05-003 Piper PA34-200T Seneca II, ZK-FMW, controlled flight into terrain, 8 km north-east of Taupō Aerodrome, 2 February 2005). The recommendation followed a similar recommendation made as a result of the Commission’s investigation into another CFIT accident two months earlier (report 04-007 Piper PA34-200T Seneca II ZK-JAN, controlled flight into terrain, Mt Taranaki/Egmont, 30 November 2004).

- Both of these earlier accidents occurred in class G uncontrolled airspace. The two recommendations recognised that the responsibility for terrain awareness in uncontrolled class G airspace remained with the pilot. The use of terrain awareness warning system equipment, like that installed in ZK-EAP and if used as intended, should have prevented these accidents.

Safety pilot

- The aeroplane was not equipped with a cockpit voice recorder, and therefore the actions of the safety pilot could not be confirmed. The responsibilities of a safety pilot were clearly defined in the operator’s procedures. Had a flight-safety-critical situation developed it would have been expected that the safety pilot would inform the pilot and ensure an appropriate response was made.

- The pilot made numerous radio calls after turning at TARUA and after descending below the 7,800-foot MSA. There was no indication of any concern being raised by either pilot during these calls. The aeroplane was equipped with a second set of flight controls, including a second radio-transmit button. This would have allowed the safety pilot to make a radio call had they wished to do so.

Emergency locator transmitter

- The Commission has investigated previous accidents where ELTs failed to operate as designed. Following an accident in 2011 the Commission made two recommendations to the CAA on the matter.41 The issue was also added to the Commissions Watchlist, under the title ‘Technologies to track and to locate’, and included rail and maritime transport as well as air.

- On 27 November 2019 the CAA issued advisory circular AC43-11 with the objective of “encourage[ing] the use of flight tracking devices and provide[ing] guidance on how to install ‘non-aeronautical’ electronic equipment safely for the purposes of tracking flight movements”. On 26 March 2021 the CAA advised that tests had been conducted on the use of a secondary antenna to help ensure geo-orbiting satellites could receive emergency signals. However, this had been found to be “suboptimal” as the signal had become degraded. In the meantime, the CAA “continues to monitor ongoing ICAO work on Emergency Locator Transmitters and supports improvements wherever possible”.

Findings Ngā kitenga

- The aeroplane was descended below the specified minimum safe altitude for the area in which the aeroplane was being flown, and a controlled flight into terrain occurred.

- The aeroplane was being flown outside the parameters required for direct navigation, having deviated from the planned track onto an unevaluated route when attempting to connect with a runway approach.

- ATS was not advised of any changes to the filed and cleared flight plan.

- The change in route was not properly validated by the pilots.

- It was very likely that the aeroplane’s terrain proximity awareness system was either excessively dimmed or not selected, so the terrain ahead was not displayed during the descent.

- There was no evidence that any malfunction or unserviceability of the aeroplane contributed to the accident.

- The pilot and safety pilot were appropriately licensed and qualified for the flight, but had little experience in night instrument-flight-rules navigation.

- The pilot’s experience and training status required appropriate supervision that should have been provided by the operator’s flight-authorisation procedures.

- The pilot did not follow the operator’s authorisation procedures.

- The operator’s flight-authorisation procedures were not sufficiently robust to prevent students and qualified pilots conducting flights without the requisite authorisation from supervising instructors.

- The added defence of having a safety pilot on board did not prevent the accident.

- The emergency locator transmitter did not function as designed

Safety issues and remedial action Ngā take haumaru me ngā mahi whakatika

General

- Safety issues are an output from the Commission’s analysis. They typically describe a system problem that has the potential to adversely affect future operations on a wide scale.

- Safety issues may be addressed by safety actions taken by a participant, otherwise the Commission may issue a recommendation to address the issue.

Robustness of flight-authorisation procedures

- The operator’s flight-authorisation processes and procedures for IFR flights were not sufficiently robust to ensure that pilots under training conducted flights with appropriate flight authorisation and supervision (including separate authorisation where needed). The operator advised that had the pilot followed the authorisation procedures as intended, it is likely that the authorising officer would have checked and challenged the route to be flown and, as likely as not, the flight would not have been approved as planned.

- The operator has completed an extensive review of its processes and procedures relating to the management, approval and supervision of training flights, and has provided evidence to the Commission of the actions taken to eliminate the weaknesses that were identified in the associated systems. The Commission believes that these actions are satisfactory in addressing the respective issues.

- The operator has taken the following safety action to address this issue:

- The operator has amended its flight-authorisation processes and procedures.

- In the Commission’s view, this safety action has addressed the safety issue. Therefore, the Commission has not made a recommendation.

Recommendations Ngā tūtohutanga

General

- The Commission issues recommendations to address safety issues found in its investigations. Recommendations may be addressed to organisations or people and can relate to safety issues found within an organisation or within the wider transport system that have the potential to contribute to future transport accidents and incidents.

- In the interests of transport safety, it is important that recommendations are implemented without delay to help prevent similar accidents or incidents occurring in the future.

New recommendations

- No new recommendations were issued.

Key lessons Ngā akoranga matua

- Pilots, especially instructor pilots, should be fully aware of the parameters prescribed by Civil Aviation Rules, including for navigating away from pre-planned and IFR-approved flight routes.

- Where possible, pilots should use and be proficient in the full capabilities of the flight instrumentation systems available to them. In this case, thorough training in the use of onboard ground-proximity conflict and warning systems, including the dimming of instrument and cockpit lights at night, would have enhanced situational awareness.

- Pilots should be aware of the consequences of, and the required validation steps (including altitude distance cross-checks) when making en-route changes to flight plans, in combination with onboard navigation systems.

- Flight training schools should ensure that their procedures for flight authorisation and supervision are sufficiently robust to ensure that students can only conduct training flights after obtaining the appropriate authorisation and supervision.

Data summary Whakarāpopoto raraunga

Details

latitude: 39° 6.0´ south

longitude: 176° 2.7´ east

Conduct of the inquiry He tikanga rapunga

- On 24 March 2019 the Rescue Coordination Centre New Zealand notified the Commission of the occurrence. The Commission subsequently opened an inquiry under section 13(1) of the Transport Accident Investigation Commission Act 1990 and appointed an investigator in charge.

- On 25 March 2019 Commission investigators travelled to Taupō. They received briefings from New Zealand Police before continuing to the accident scene to conduct the site investigation. At the same time a Commission investigator travelled to Auckland and interviewed the operator’s senior staff and the aeroplane occupants’ next of kin.

- In accordance with Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, the Commission notified the state of manufacture of the aircraft and engines, the BFU. On 28 March 2019 the BFU appointed an accredited representative for France and appointed Technify Motors as its technical adviser.

- On 4 April 2019 the wreckage of the aeroplane was removed from the accident scene and relocated to the Commission’s secure facility in the Wellington region.

- On 10 May 2019 the two engine-control units from the aeroplane’s FADEC system were sent to the BFU, where the data was downloaded and analysed.

- On 7 June 2019 the Commission received a copy of the operator’s internal investigation report.

- On 27 January 2021 the operator provided the Commission with evidence of how it had addressed the recommendations contained in its internal investigation report.

- Between 26 March and 6 April 2021, the CAA provided an update on activities relating to the recommendations referred to in paragraphs 3.36 and 3.37, ELT reliability data following fatal accidents since 2011 and other safety initiatives.

- On 28 April 2021 the Commission approved a draft report for circulation to five interested persons for their comment. The Commission received three responses, while the remaining two advised that they had no comments to make. As a result of the responses, further enquiries were made of Airways New Zealand, the CAA and Air Services Australia. Changes have been incorporated in this final report as a result.

- On 22 September 2021, the Commission approved the final report for publication.

Glossary Kuputaka

- Direct routing

- When an aircraft is flown along a route that has not been charted and has not been evaluated. Sometimes referred to as ‘random routing’

- Flight information officer

- Airways New Zealand provides a flight information service through a flight information officer, who offers limited assistance for pilots operating in uncontrolled airspace. The pilots remain responsible for terrain-conflict avoidance and separation from other aircraft

- Instrument flight rules

- Rules that allow properly equipped aircraft to be flown under ‘instrument meteorological conditions’ (conditions expressed in terms of visibility, distance from cloud, and ceiling less than the minima specified for visual meteorological conditions)

- Minimum safe altitude

- The lowest altitude which may be used which will provide a minimum clearance of 1,000 feet (300 m) above all objects located in the area contained within a sector of a circle of 46 km (25 nautical miles) radius centred on a radio aid to navigation (ICAO)

- Missed approach

- The phase of an instrument approach when an aircraft overshoots from the approach and climbs back to a safe altitude

- Reporting point

- Sometimes termed waypoints. Reporting points can be compulsory or non-compulsory

- Terminal arrival altitude

- A terminal arrival altitude provides a transition from an en-route structure to an approach procedure

- Top of descend

- When an aircraft transitions from the cruise phase of flight and starts to descend for the approach.

- Uncontrolled class G airspace

- Under ICAO Annex 11 and New Zealand Civil Aviation Rules Part 71 – Designation and Classification of Airspace, airspace is divided into seven classifications: classes A to G. Class G is uncontrolled airspace. Classes B, E and F are not available in New Zealand

Appendix 1. Timeline