At about 1147 on 13 April 2023, the recreational vessel Onepoto and the passenger ferry Waitere collided in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand. The Onepoto was travelling from Opua to Onepoto Bay, while the Waitere was operating a scheduled service from Russell to Paihia. The master of the Waitere sustained serious injuries and was airlifted to hospital. The ferry suffered catastrophic damage and later sank, while the Onepoto received some damage but was able to continue under its own power to a repair berth.

Executive summary Tuhinga whakarāpopoto

What happened

- At about 1147 on 13 April 2023, the recreational vessel Onepoto and the passenger ferry Waitere collided in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand. The Onepoto was on passage from Opua to Onepoto Bay. The Waitere was on a scheduled trip from Russell to Paihia.

- The master of the Waitere suffered serious injuries and was airlifted to hospital.

- The Waitere suffered catastrophic damage and eventually sank. The Onepoto also sustained some damage but was able to proceed under its own power to a repair berth.

Why it happened

- Watchkeeping standards on both vessels did not provide safe navigation and it is virtually certain that they contributed to the accident.

- The skipper of the Onepoto was distracted by a non-critical engine alarm. As a result, they did not keep a proper lookout and did not see the Waitere crossing in front of them. Once the skipper of the Onepoto noticed the Waitere, they were too close to take action to avoid the collision.

- The skipper of the Onepoto was navigating the vessel at 20.5 knots (kt). Had it been travelling at a safer speed for the conditions, it is very likely that either the collision would have been avoided or the consequences of the collision would have been reduced.

- The master of the Waitere did not see the Onepoto until it was about five metres (m) away, and they did not have enough time to take action to avoid the collision.

What we can learn

- Collisions at sea can be avoided by implementing watchkeeping standards and adhering to the collision prevention rules.

- Every vessel must maintain a proper lookout by sight and hearing and use all means available to determine whether a risk of collision exists. In a crossing situation, regardless of which vessel is the designated give-way vessel, both vessels must be vigilant and monitor the effectiveness of any avoidance action taken, such as a change of course and/or a change of speed, until the other vessel has passed and is clear.

- All vessels must proceed at a speed that allows time to determine whether a risk of collision exists and enables the vessel to stop in a safe distance if required.

Who may benefit

- All seafarers, vessel owners, vessel operators, boat insurers, boat clubs, local councils and harbourmasters may benefit from the findings of this inquiry.

Factual information Pārongo pono

Narrative

- At approximately 0707 on 13 April 2023, the Onepoto departed Onepoto Bay with the skipper at the helm and a passenger. They planned to go to the Bay of Islands Marina at Opua for scheduled maintenance work, stopping at Russell for fuel enroute (see Figure 4).

- The vessel arrived at the Bay of Islands Marina at about 0842. It was met by a marine radio technician contracted to retrofit a new very high frequency (VHF) marine radio. Because of illness, an engine technician who had been engaged to complete engine diagnostics was unable to attend.

- At approximately 1124, the skipper of the Onepoto completed a pre-departure radio check with Russell Radio using the new VHF radio. About a minute later, the skipper steered the vessel clear of the Bay of Islands Marina breakwater and headed across the Kawakawa River towards Waikare Inlet.

- At approximately 1129, the Onepoto passed south of Motutokape Island and entered the Waikare Inlet, at speeds between 5 kt and 10 kt, before altering course to head towards the Veronica Channel.

- While entering and exiting the inlet and while transiting the designated yacht mooring area north of Motutokape Island, the skipper of the Onepoto operated the vessel at speeds between 10 kt and 15 kt, which were above the 5 kt speed limit for that area.

- At approximately 1140, the Onepoto passed abeam of Tapu Point and the skipper increased the Onepoto’s speed to about 20 kt. The vessel was still within the 5 kt speed limit zone.

- About a minute later the Onepoto was in the main Veronica Channel and more than 200 m from land, where there were no speed restrictions.

- At approximately 1140, the ferry Waitere, with 20 people on board (15 adult passengers, 4 children and the master), departed the wharf at Russell on its scheduled service to Paihia at a speed of about 5 kt (see Figure 4). As it passed the 5 kt speed limit zone the master increased the vessel’s speed to maximum, which was about 6 kt.

- In the logbook, the master of the Waitere had recorded 16 passengers for that scheduled service to Paihia.

- At approximately 1145, as the Onepoto passed west of Toretore Island, an alarm sounded on the vessel’s engine-monitoring system.

- The Onepoto was approaching the Bay of Islands ferry route (see Figure 4). Three ferry services operated on this route, on a Northland Regional Council public transport timetable. There were no speed restrictions for this area.

- The Onepoto skipper maintained a speed of about 20 kt and investigated the cause of the alarm on the engine-monitoring system display, located on the helm station in front of the skipper (see Figure 5). They worked through the system menus on the display, determining that it was a non-critical low voltage alarm.

- During interview, the skipper of the Onepoto stated that when they looked up they saw the Waitere crossing. The skipper determined there was not enough time to alter course to avoid collision, so they pulled the Onepoto’s engine throttles to stop and then to astern.

- During interview, the master of the Waitere stated that they only saw and heard the Onepoto when it was a few metres away and they did not have time to take any action to avoid collision.

- At approximately 1147, the two vessels collided. The Onepoto struck the port side of the Waitere and the impact caused the Onepoto to run on top of the Waitere, near the wheelhouse. The master of the Waitere, who was positioned at the helm in the wheelhouse, was seriously injured. One of the passengers from the Waitere jumped into the water on impact.

After the collision

- A few moments later the Onepoto stopped moving ahead and slid back into the water with its engines going astern. The skipper manoeuvred the Onepoto away from the Waitere and stopped.

- Several passengers on the Waitere went to the wheelhouse and removed wooden debris to enable the injured master to be attended to by a passenger who was a doctor. Passengers tried to locate lifejackets but were unable to find any.

- The Waitere engine remained running and propelling the vessel ahead. The passengers did not know how to stop it.

- Between 1149 and 1152, several passengers from the Waitere made 111 calls to report the accident and advise that the master of the Waitere was injured. An ambulance and the Police were dispatched to Paihia.

- The Waitere’s shore-based designated search and rescue (SAR) person was not immediately aware of the accident. They became aware of the accident later via social media. This resulted in a delay in communicating the number of people on board the Waitere to the vessels responding to the accident.

- At approximately 1157, the skipper of the Onepoto called Russell Radio on the VHF radio to report the collision, and that one person on the Waitere was injured and one passenger was in the water. The skipper of the Onepoto then retrieved the passenger from the water.

- At approximately 1158 the ferry Waimarie, on its scheduled trip from Paihia to Russell, saw the damaged Waitere and stopped to assist.

- The master of the Waimarie rafted up to the Waitere and instructed a passenger on how to stop the Waitere’s engine and to drop the anchor. The master of the Waimarie then guided the passengers over to the Waimarie.

- At approximately 1205, Russell Radio contacted the Bay of Islands Coastguard and notified it of the collision. Coastguard started mobilising crew and preparing the Coastguard vessel BR2.

- A parasailing vessel operating in the vicinity heard the VHF call from the Onepoto skipper to Russell Radio and arrived at the accident site shortly after the Waimarie. Two passengers on the parasailing vessel were nurses and were able to help the doctor to transfer the injured master to the parasailing vessel.

- At approximately 1210, the parasailing vessel and the Onepoto proceeded towards Paihia. At about the same time the Police requested a medevac helicopter.

- Upon arriving at Paihia, the parasailing vessel and the Onepoto were met by the Police and paramedics. The paramedics attended to the injured master.

- The skipper of the Onepoto was immediately interviewed by the Police and volunteered an alcohol test, which was negative.

- At approximately 1305, the Coastguard vessel BR2 arrived at the anchored Waitere. They reported that there were no people onboard, and that the vessel had extensive damage extending up to the waterline and was possibly taking on water (see Figure 6 and 7).

- A second Coastguard vessel, Kokako, arrived at the accident site and stayed with the damaged ferry. The Coastguard vessel BR2 did not have access to a passenger count and so started a search of the immediate area looking for any passengers in the water.

- At approximately 1316, a Medevac helicopter arrived at Paihia.

- The Coastguard crew boarded the Waitere and set up a salvage pump to discharge water, but the pump was unable to keep up with the water ingress and the Waitere sank at approximately 1408.

- At approximately 1413, the medevac helicopter departed for Middlemore Hospital with the injured master.

- On 15 April 2023, the sunken wreck of the Waitere was refloated and taken to the Bay of Islands boatyard at Opua.

The Waitere

- The Waitere was a 14.01 m wooden passenger ferry built in 1944 with a 111.3 hp (83 kW) engine. The vessel, known locally as the Blue Ferry, was owned and operated by Waitere Cruises Limited (Waitere Cruises) (Waitere Cruises Limited was removed from the Companies Office Register on 20 October 2023).

- The Waitere was one of three ferries that operated on a Northland Regional Council public transport timetable, running a regular hourly service between Russell and Paihia from September to May every year. The Waitere started its first service from Russell at 0940 and departed Paihia for its last service at 1710. Each trip took approximately 20 minutes.

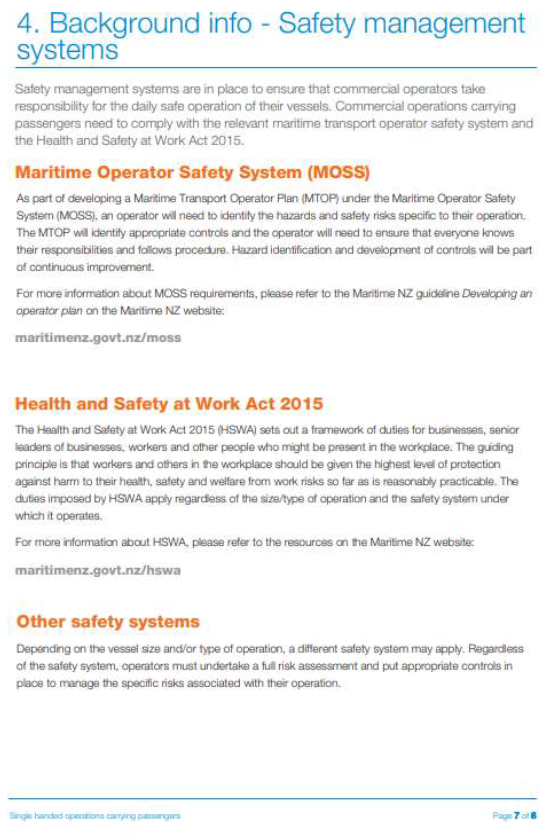

- The Waitere could carry a maximum of 60 passengers and the minimum safe crewing document required the vessel to have a minimum crew of one, namely the master (see Appendix 1, showing Table 11 of Maritime Rule Part 31.84(4)(b)).

- Waitere Cruises operated under the Maritime Operator Safety System (MOSS) as specified by Maritime Rule Part 19: Maritime Transport Operator – Certification and Responsibilities.

- The master of the Waitere had operated the vessel for 25 years and held a valid Master of Restricted-Limit Launch qualification (Skipper Restricted Limits <24m with passenger endorsement has superseded the Master of Restricted-Limit Launch qualification, which has been grandfathered over).

The Onepoto

- The Onepoto was a 9.74 m recreational vessel built by Boston Whaler in 2011 and equipped with two 300 hp outboard engines.

- The skipper of the Onepoto had completed an optional training course (see paragraph 2.69) and held a Boatmaster Certificate (a non-commercial certificate issued by Coastguard). They had operated the Onepoto for about nine years.

Site and wreckage information

- As a result of the collision, the Waitere suffered extensive damage: the wheelhouse was completely destroyed (see Figure 6) and the hull sustained damage on the port side just below the waterline (see Figure 7).

- The Onepoto sustained damage to the bow, anchor pulpit and stainless-steel bow rail (see Figure 8). There was some gouging of the fibreglass under the waterline, but there was no water ingress. The skipper of the Onepoto was able to manoeuvre the vessel under its own power and returned to the Bay of Islands Marina after the accident.

Recorded data

- The GPS data from the Onepoto was recovered and downloaded. This information was used to recreate the vessel’s track and speed leading up to the collision.

- The Waitere did not have a GPS device onboard.

Meteorological and ephemeral information

- It was a bright sunny day, with a few clouds and good visibility.

- The sea was calm, and the prevailing wind was a gentle north-westerly breeze of about 10 kt (according to the Beaufort wind force scale, which describes wind intensity based on observed sea conditions).

The collision prevention framework

The COLREGs and Maritime Rules

- The Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (the COLREGs) was introduced by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in 1972. The COLREGs set out, amongst other things, navigation rules to be followed by vessels to prevent collisions between two or more vessels.

- Maritime Rule Part 22: Collision Prevention have given effect to the COLREGs in New Zealand. Part 22 applies to all New Zealand ships, wherever they are, and to all foreign ships when they are in New Zealand waters.

-

In addition, the Northland Regional Council Navigation Safety Bylaw 2017 includes the following Collision prevention bylaw:

3.16 Collision prevention

3.16.1 No person shall operate any vessel in breach of Maritime Rule 22 (Collision Prevention), made under the Maritime Transport Act 1994.

3.16.2 Every person commits an offence against this bylaw who, when required to do anything by an officer of the council under clause 3.16.1 of this bylaw, fails to comply with that requirement as soon as is reasonably possible.

3.16.3 Every vessel must at all times maintain a proper lookout by sight and hearing as well as by all available means appropriate to the prevailing circumstances and conditions, so as to make a full appraisal of the situation and the risk of collision.

Maritime Rule 22.5: Look-out

- Maritime Rule 22.5 states that every vessel must at all times maintain a proper lookout by sight and hearing as well as by all available means appropriate in the prevailing circumstances and conditions, so as to make a full appraisal of the situation and the risk of collision.

- The skipper of the Onepoto and the master of the Waitere were both in control of power-driven vessels making way through the water. They were required to keep a proper lookout for other vessels and, if a risk of collision existed, take appropriate action to avoid collision.

Maritime Rule 22.15: Crossing Situation

- Maritime Rule 22.15 addresses a crossing situation. When the paths of two power-driven vessels are crossing, creating risk of collision, the vessel that has the other on its own starboard side must keep out of the way. The vessel required to keep out of the way must, if the circumstances of the case allow, avoid crossing ahead of the other vessel (see Figure 9).

- The Onepoto was on a northerly course at a speed of approximately 20.5 kt. The Waitere was on a southwesterly course at a speed of approximately 6 kt, and on the starboard side of the Onepoto. The Onepoto was the give-way vessel, and the Waitere was the stand-on vessel.

Action by the give-way vessel

- Maritime Rule 22.16 states that “every vessel that is directed to keep out of the way of another vessel must, so far as possible, take early and substantial action to keep well clear.”

Action by the stand-on vessel

- The stand-on vessel is required to maintain its course and speed and monitor the give-way vessel. If the give-way vessel is not taking appropriate actions to avoid collision the stand-on vessel must take action to avoid collision.

-

Maritime Rule 22.17 states:

(1) If one of two vessels is to keep out of the way, the other must keep its course and speed.

(2) As soon as it becomes apparent to the stand-on vessel that the vessel required to give way is not taking appropriate action in compliance with this Part—

- it may take action to avoid collision by its manoeuvre alone; and

- if it is a power-driven vessel in a crossing situation, if the circumstances of the case allow, it must not alter course to port for a vessel on its own port side.

(3) When, from any cause, the stand-on vessel finds itself so close that collision cannot be avoided by the action of the give-way vessel alone, it must take whatever action will best avoid collision.

(4) This rule does not relieve the give-way vessel of its obligation to keep out of the way.

Figure 9: Action to be taken in a crossing situation

The Maritime Operator Safety System

- The Maritime Operator Safety System (MOSS) was implemented on 1 July 2014 as a new regulatory system for maritime safety. MOSS was introduced to improve safety and protection of the marine environment associated with domestic commercial vessels in New Zealand.

- Under MOSS, an operator is required to develop and prepare a Maritime Transport Operator Plan (MTOP) for each vessel they operate (Maritime Rule 19.41). The MTOP details specific risks associated with the operator’s intended maritime transportation activities and procedures and controls to mitigate these risks.

- The MTOP is assessed by Maritime New Zealand to ensure that the various components, such as risk management, training and maintenance, are included. Additionally, Maritime New Zealand conducts a site visit, in which the operator demonstrates the various aspects of the MTOP, to ensure they are appropriate.

- The Director of Maritime New Zealand must grant a Maritime Transport Operator Certificate (MTOC) if they are satisfied that the operator’s MTOP has met all the requirements specified in Maritime Rule Part 19 (Maritime Rule 19.22) and the Maritime Transport Act 1994 section 41 (Maritime Transport Act 1994, section 41: Issue of maritime documents and recognition of documents). The MTOC is valid for ten years.

- It is the operator’s responsibility to ensure that the MTOP is a living document, by assessing risks and addressing them as they arise (Maritime Rule 19.61 (b)). Maritime New Zealand conducts periodic MOSS audits to assess how the operator is performing against the vessel’s MTOP. The initial MOSS audit is usually done within 18 months of the operator coming into the system. A risk-profiling tool is used after each MOSS audit to determine the operator’s risk profile, and to determine the date by which the next audit must be completed. The maximum time between two audits is 48 months.

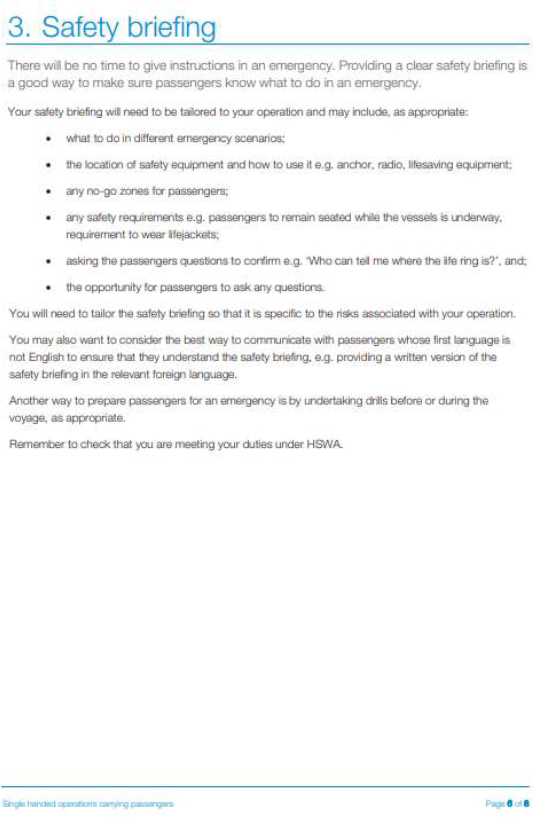

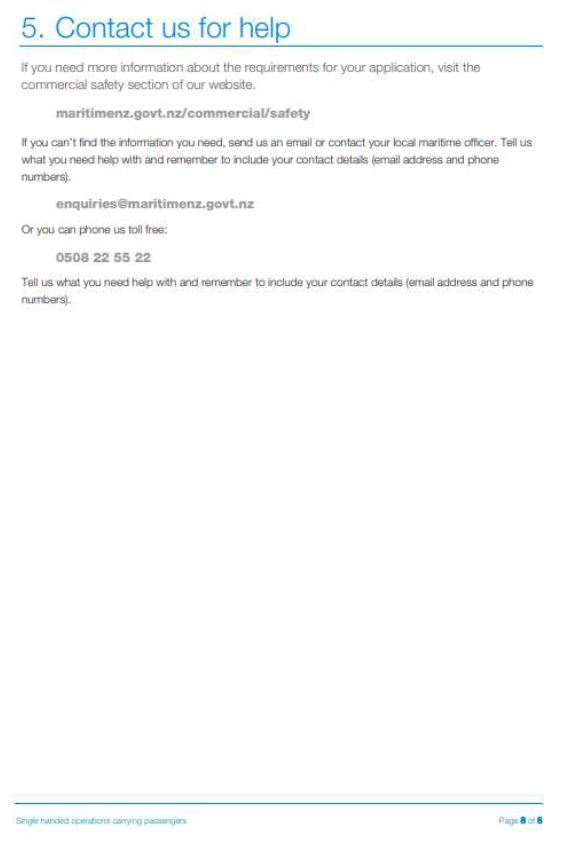

Safety briefings for ferries

- The Maritime Rules prescribe the operating and training procedures to manage emergency situations aboard vessels or to prevent such situations occurring (Maritime Rules Part 23: Operating Procedures and Training).

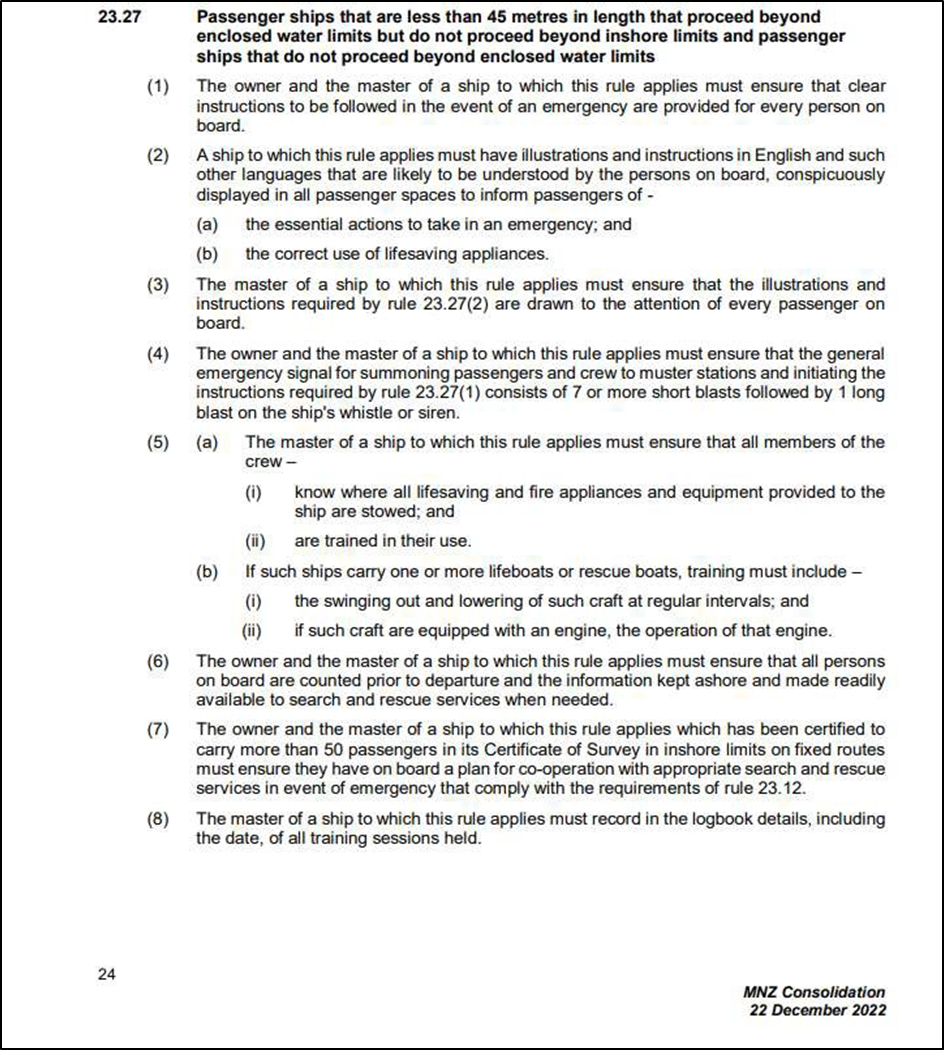

- Under the Maritime Rules, the master’s responsibilities included the safety and wellbeing of the passengers. The master was required to provide every person on board with clear instructions on the procedures to be followed in case of an emergency (Maritime Rule 23.27). Illustrations and instructions for the correct use of life-saving appliances and for essential actions to be taken in an emergency had to be conspicuously displayed on the vessel. The master had to ensure that every passenger had been made aware of the posted instructions. (See Appendix 2 Maritime Rule 23.27.)

- In September 2019, Maritime New Zealand published a guideline for Single handed operations carrying passengers (see Appendix 3). This guideline recognised that there would be no time to give instructions in an emergency; therefore providing a clear safety briefing was a good way to make sure passengers knew what to do in an emergency

- The guideline emphasised that safety briefings needed to be tailored to the specific operation. The safety briefings could include safety equipment and how to use it and were an opportunity to inform passengers of ‘no go’ areas and other hazards specific to the vessel and operation.

Recreational boat skipper competence and training

- In New Zealand, there is no requirement for the skipper of a recreational vessel to have any formal training or certification. However, there was an optional Day Skipper course and a Boatmaster Certificate course available.

- The objective of the Day Skipper course was to provide all the basic knowledge needed to help recreational vessel users understand the maritime environment, the rules of the sea, boats and their capabilities, and dealing with emergencies.

- The Boatmaster Certificate course was for recreational vessel users with current knowledge and experience. It covered a wide range of vessels, including yachts, launches and powerboats. The training was intended to extend the participant’s current knowledge in chartwork, navigation techniques, distress signals, emergency procedures, knots and rope work, and provide a thorough explanation of the rules at sea including proper lookout duties and collision avoidance.

- Maritime New Zealand recommends that skippers undertake some form of boating education to understand the Maritime Rules.

- The skipper is responsible for the safety of the vessel and its occupants and for complying with all the relevant Maritime Rules, regulations and Regional Council bylaws.

Safe speed

- At all times every vessel must proceed at a safe speed, so that proper and effective action to avoid collision can be taken, and the vessel can be stopped within a distance appropriate to the prevailing circumstances and conditions (Maritime Rule 22.6). These conditions can include visibility, sea conditions, navigational hazards, distractions, and other marine traffic.

- Maritime New Zealand recommends that skippers operate their vessels at a safe speed by slowing down in situations in which it may be difficult to see another boat (eg, in waves, rain, fog or when there may be glare on the water).

- The maximum speed permitted for all vessels in the Bay of Islands region is 5 kt when within 200 m of shore or any vessel with a dive flag, and within 50 m of any other boat or swimmer.

- The speed of vessels in the accident area was also prescribed in the Northland Regional Council Navigation Safety Bylaw 2017, clause 3.2.1 (see Figure 10).

Analysis Tātaritanga

Introduction

- The following section analyses the circumstances surrounding the event to identify those factors that increased the likelihood of the event occurring or increased the severity of its outcome. It also examines any safety issues that have the potential to adversely affect future operations.

- Both vessels were compliant with all relevant maritime legislation for their type and operation and no mechanical or equipment failure contributed to the accident.

- The immediate cause of the collision was poor watchkeeping by the people in charge of both the vessels. Two sets of circumstances increased the risks, namely the Onepoto was travelling at a speed that was unsafe for the changed conditions, and Waitere’s MTOP, and Maritime New Zealand’s assessment of it, were not fit for purpose in supporting safe operations of a passenger ship.

- The Onepoto on a northerly course and the Waitere on a southwesterly course were in a crossing situation. Neither the skipper of the Onepoto (the give-way vessel) nor the master of the Waitere (the stand-on vessel) had sighted or heard the other vessel approaching. As a result, they had not assessed whether a risk of collision existed and did not take appropriate actions.

- During interview, the skipper of the Onepoto stated that they were distracted for a few seconds by an alarm on the vessel’s engine monitoring system. When the skipper attended to the alarm, their attention was divided between resolving the alarm, controlling the vessel and continuing to keep a lookout. This compromised the skipper’s ability to keep a proper lookout. When the skipper then looked up again, it was the first time they noticed the Waitere crossing.

- The skipper of the Onepoto was aware that they were approaching the ferry-crossing route as they had crossed paths with the ferries on previous visits to Russell. The skipper had not considered adjusting the Onepoto’s speed to a safer speed while they resolved the engine alarm.

- Had the skipper of the Onepoto considered all factors affecting safe speed they may have reduced the vessel’s speed accordingly. A reduction in speed would very likely have allowed the skipper enough time to avoid the collision.

- During interview the master of the Waitere stated that the visibility was perfect. They had the port side wheelhouse door open, and they were looking out of the wheelhouse windows. When they saw and heard the Onepoto it was just a few metres away.

- Ferry masters should be vigilant for northbound or southbound vessels, especially when crossing the Veronica Channel, in order to monitor developing situations. People in charge of other vessels in the vicinity of the ferry route should also be vigilant for crossing ferries.

- While acknowledging the speed difference between the two vessels and the effect this may have had on their ability to avoid the collision, this does not detract from the Commission’s finding that had a proper lookout been kept on both vessels, it is virtually certain that action to avoid collision in accordance with the Maritime Rules, would have been taken by one or both vessels, and either the collision would have been avoided or the consequences of the collision would have been reduced.

MTOP not fit for purpose

Safety issue: The Maritime Transport Operator Plan (MTOP), prepared by Waitere Cruises Limited and assessed by Maritime New Zealand as part of the Maritime Transport Operator Certificate (MTOC) certification process, was not fit for purpose and therefore did not sufficiently support safe operations. In particular, the MTOP:

(1) omitted procedures for safe watchkeeping and keeping a proper lookout

(2) contained ambiguities and irrelevant and inaccurate information

(3) did not identify and mitigate the risk of the sole-charge master being incapacitated.

-

The MTOP prepared by Waitere Cruises Limited included information that was not relevant to their maritime operations, while at the same time omitting procedures for watchkeeping and managing risks identified in Maritime New Zealand’s guidance publication.

(i) The Waitere’s MTOP omitted procedures for safe watchkeeping and keeping a proper lookout

- Keeping a safe navigational watch includes actively monitoring the vessel’s position, track, speed, stability, propulsion system and the VHF radio, and keeping a proper lookout.

- Keeping a proper lookout means to actively monitor what is happening around the vessel by sight and hearing and, if electronic navigation aids are available, to use them appropriately when underway.

-

The standing orders in the Waitere’s MTOP included one statement relating to watchkeeping: “Keep a proper lookout at all times.” There were no procedures or guidance for master’s regarding the basic principles of keeping a navigational watch or proper lookout, such as maintaining a continuous state of vigilance by sight and hearing to make a full appraisal of the risk of collision, stranding and other dangers to navigation.

(iii) The Waitere’s MTOP contained ambiguities and irrelevant and inaccurate information

- The Commission found that the Waitere’s MTOP contained ambiguities and irrelevant and inaccurate information, including:

-

The MTOP was ambiguous with respect to safety briefings. One section stated that before starting a trip all passengers would be briefed on safety procedures. Another section stated that no verbal briefing was required but that the master controlled the entrance to the vessel and could indicate appropriate information to the passengers. The Passenger Policy section contained instructions for a passenger safety briefing before starting a trip. It stated that if the weather deteriorated, further instructions were to be given to passengers including instructions on donning lifejackets, but the vessel had no lifejackets for passengers. Lifejackets were only available for the crew. The Passenger Safety Briefing section stated that as the vessel was a public transport vessel no verbal safety briefing was required.

-

The MTOP Emergency Preparedness procedures for Overdue Ship or Stricken Vessel were not relevant to a vessel operating in enclosed waters on 20-minute trips; the procedures were for vessels that operated beyond enclosed waters. This oversight was not identified and amended during subsequent MOSS audits and MTOP reviews.

-

The MTOP did not include procedures to comply with Maritime Rule 23.27(6), which required that the master count the number of passengers onboard and record that information ashore. There was no evidence that the number of passengers for each trip was recorded ashore. Immediately after the accident the local emergency services, Bay of Islands Coastguard and Russell Radio were not aware of the number of passengers onboard.

-

The MTOP recorded the minimum crewing numbers as one crew and the maximum number of passengers as 60. The MTOP stated that “Extra crew is used when required to assist passengers”, but there was no supporting information on when this applied or how this would be implemented.

-

The instructions for the master and crew implied that there was always more than one crew member on board, despite there only being the master onboard the Waitere.

-

The standing orders section in the MTOP was poorly written and referred to the vessel’s radar, a Global Positioning System (GPS) and a plotted track for steaming, none of which were on the vessel.

(iii) The Waitere’s MTOP did not identify and mitigate the risk of the sole-charge master being incapacitated

- The Waitere’s MTOP contained a Hazard Identification and Control Register, which included Navigation hazards – Collision and Groundings as possible with extreme consequences. The risk controls that had been put in place relied on the sole-charge master managing the risk.

- The risk of the sole-charge master being incapacitated was not identified in the Hazard Identification and Control Register and was not mitigated.

- Maritime New Zealand’s guideline for Single handed operations carrying passengers encouraged operators to consider specific risks associated with relying on passengers to contribute to an emergency response when an operation is run by a single person (see Appendix 3).

- This guideline reflected Maritime Rules Part 23, which prescribes various operating and training procedures to be implemented to manage emergency situations or to prevent such situations occurring.

- On the morning of the accident the Waitere departed Russell wharf with 19 passengers onboard, including 4 children. None of the passengers interviewed by the Commission remembered a safety briefing being conducted before departure or whether any instructions were provided by the master as they boarded the vessel.

- The collision incapacitated the master, resulting in the passengers being left to manage themselves in a situation that they were not familiar with.

- Soon after the collision, there was panic among Waitere’s passengers as they searched for lifejackets and buoyancy aids. The Waitere did not carry lifejackets for the passengers. The vessel had four lifebuoys on board, which were not suitable for small children, and six ridged buoyant life-saving pontoons located on the vessel’s canopy, which the passengers did not know how to deploy. A safety briefing would have helped to mitigate some of the challenges faced by the passengers.

- The collision destroyed the wheelhouse of the ferry, including the control panel. The engine was still running after the collision, and the vessel was making way through the water. One passenger managed to pull the throttle back, but none was able to stop the engine immediately following the collision.

- The lack of a safety briefing did not contribute to the collision; however, it was another factor that increased risk to the passengers following the collision.

- As Waitere Cruises is no longer operating, the Commission has not made any recommendations with respect to their MTOP.

Maritime New Zealand’s MTOP assessment process

- In 2017, Waitere Cruises developed an MTOP and provided it to Maritime New Zealand for assessment. Having assessed the MTOP, Maritime New Zealand issued an MTOC to Waitere Cruises, valid for ten years.

- It is the operator’s responsibility to ensure that the MTOP is a living document by assessing risks and addressing them as they arise. Any updates to the MTOP are documented on the MTOP Update Record (see Figure 11).

- Maritime Officers from Maritime New Zealand conduct periodic MOSS audits to verify how an operator has performed against their MTOP. Maritime New Zealand had conducted a MOSS audit in November 2018 and as a result Waitere Cruises was considered a low-risk operation. This qualified it to conduct a self-audit, which was scheduled for November 2021. Self-audits were adopted during COVID as an interim measure and were not carried out frequently.

- The self-audit was completed in November 2021 (see Figure 12) using an audit template provided by Maritime New Zealand. Section 12 of the audit template addressed the procedures for emergencies but did not include a safety briefing or emergency procedures in the event of an incapacitated master, as highlighted in the guideline for Single handed operations carrying passengers. Had the audit template been amended to included emergency procedures related to single-person operations carrying passengers, it may have prompted the operator to review its procedures regarding passenger safety briefings and an incapacitated master.

- A recommendation has been made to Maritime New Zealand to review its process of assessing MTOPs to ensure they are satisfied that vessels included in the MTOP will be operated in accordance with safety systems that are specific and appropriate to their maritime transport operations.

Speed – a factor that increased risk

- When the skipper of the Onepoto looked down to investigate the alarm on the engine-monitoring system, the Onepoto was approximately 0.68 nm from the ferry-crossing track and, travelling at a speed of 20.5 kt, it would take approximately 2 minutes to cover that distance (see Figure 13).

- Although there was no speed restriction in this area, there were factors present that should have influenced the skipper’s assessment of a safe speed, namely the approach to the ferry-crossing track and the presence of an unresolved engine-monitoring alarm.

- When the vessels were within 50 m of each other, each vessel should have been travelling at a speed of no more than 5 kt, in accordance with the Northland Regional Council Navigation Safety Bylaws 2017 (see Figure 10).

- If the Onepoto had been travelling at a safer speed for the conditions, it is very likely that either the collision would have been avoided or the consequences of the collision would have been reduced.

Findings Ngā kitenga

- Immediately before the collision, neither the skipper of the Onepoto nor the master of the Waitere was keeping a proper lookout. Had a proper lookout been kept on both vessels so that detection and assessment of the risk of collision had occurred, it is virtually certain that action would have been taken by one or both vessels, and either the collision would have been avoided or the consequences of the collision would have been reduced.

- If the Onepoto had been travelling at a safer speed for the conditions, it is very likely that either the collision would have been avoided or the consequences of the collision would have been reduced.

- The skipper of the Onepoto, the give-way vessel, was distracted by an engine alarm and did not see the Waitere until it was too late and therefore was unable to take early and substantial action to keep well clear.

- The master of the Waitere, the stand-on vessel, did not see or hear the Onepoto until it was only a few metres away and did not take any action to avoid collision when the Onepoto did not give way.

- There was no safety briefing for passengers on board the Waitere and the MTOP was ambiguous as to whether a safety briefing was required.

- The Waitere’s MTOP was not fit for purpose and did not support the safe operation of a ferry passenger service, relying on one person (the master) to manage the safety of the passengers in an emergency.

- Vessels in the area responded quickly to the collision, which resulted in all passengers being safely rescued and transferred ashore.

Safety issues and remedial action Ngā take haumaru me ngā mahi whakatika

General

- Safety issues are an output from the Commission’s analysis. They may not always relate to factors directly contributing to the accident or incident. They typically describe a system problem that has the potential to adversely affect future transport safety.

- Safety issues may be addressed by safety actions taken by a participant. Otherwise, the Commission may issue a recommendation to address the issue.

- One safety issue was identified in this investigation.

Safety issue: The Maritime Transport Operator Plan (MTOP), prepared by Waitere Cruises Limited and assessed by Maritime New Zealand as part of the Maritime Transport Operator Certificate (MTOC) certification process, was not fit for purpose and therefore did not sufficiently support safe operations. In particular, the MTOP:

(1) omitted procedures for safe watchkeeping and keeping a proper lookout

(2) contained ambiguities and irrelevant and inaccurate information

(3) did not identify and mitigate the risk of the sole-charge master being incapacitated.

- On 9 June 2024, Maritime New Zealand informed the Commission that it fully appreciates the critical importance of effective watchkeeping practices and that they have had a strong focus on watchkeeping practices, working with industry over many years. Some of their initiatives are:

- regularly targeting watchkeeping and lookout practices in MOSS audits

- releasing new guidance on lookout requirements in February 2024, and watchkeeping guidance for commercial vessels in April 2024

- utilising an enforceable undertaking to trigger the development of new digital and practical learning modules on watchkeeping and bridge management

- prosecuting operators involved in particularly egregious incidents in which poor watchkeeping practices have played a role.

- Maritime New Zealand also agreed that the Waitere’s MTOP contained a number of gaps. Maritime New Zealand stated that their practices around MTOC certification and audit processes had significantly evolved since the Waitere’s MTOP was last assessed. Some of the changes that Maritime New Zealand have made are:

- self-audits for MTOPs are no longer used by Maritime New Zealand

- as a result of the revised practice, Maritime New Zealand believes it would be well placed to work with operators on shortfalls of future audits

- improvements in their risk assessment process

- continually looking for opportunities within their revised processes to ensure MTOPs are of a high standard.

- In the Commission’s view, these safety actions have addressed the safety issue. Therefore, the Commission has not made a recommendation.

Recommendations Ngā tūtohutanga

General

- The Commission issues recommendations to address safety issues found in its investigations. Recommendations may be addressed to organisations or people and can relate to safety issues found within an organisation or within the wider transport system that have the potential to contribute to future transport accidents and incidents.

- In the interests of transport safety, it is important that recommendations are implemented without delay to help prevent similar accidents or incidents occurring in the future.

- As Waitere Cruises is no longer operating, the Commission has not made any recommendations with respect to the Waitere’s MTOP.

- In the Commission’s view, safety actions implemented by Maritime New Zealand have addressed the identified safety issue. Therefore, the Commission has not made any recommendations with respect to Maritime New Zealand’s practices around MTOC certification and audit processes.

New recommendation

- The Commission issued no new recommendations.

Key lessons Ngā akoranga matua

- All vessels must maintain a proper lookout and use all means available to determine whether a risk of collision exists. Regardless of which vessel is designated to act, both vessels must check the effectiveness of the action taken, until the danger has gone.

- All vessels must proceed at a speed that enables the vessel to stop in a safe distance or allows time to assess the situation and take corrective action.

- Conducting a safety briefing and providing passengers with clear instructions is key to ensuring their safety in an emergency.

- The Maritime Transport Operator Plan (MTOP) is a living document. It is the operator’s responsibility to periodically review the MTOP, to ensure that it remains current, manages operational risks and is fit for purpose.

Data summary - Vessel particulars for the Waitere Whakarāpopoto raraunga

Details

Data summary - Vessel particulars for the Onepoto Whakarāpopoto raraunga

Details

Conduct of the Inquiry Te whakahaere i te pakirehua

- On 13 April 2023, Maritime New Zealand notified the Commission of the occurrence. The Commission subsequently opened an inquiry under section 13(1) of the Transport Accident Investigation Commission Act 1990 and appointed an Investigator-in-Charge.

- The Commission issued a protection order under section 12 of the Transport Accident Investigation Commission Act 1990 in relation to the vessels involved in the accident, the passenger ferry Waitere and the recreational vessel Onepoto. It was issued to preserve and protect evidence from both vessels, and to prevent the tampering with, or removal of, any items from the vessels.

- On 15 April 2023, the sunken Waitere was salvaged. The Onepoto and the Waitere were stored on hard stands at the Bay of Islands Marina, Opua.

- On 23 August 2023, the protection order was amended to remove the Waitere. The wreck was handed over to the insurers.

- On 28 September 2023, the protection order was revoked and the Onepoto was handed over to the insurers.

- On 24 April 2024, the Commission approved a draft report for circulation to four interested parties for their comment.

- Two interested parties provided a detailed submission and one interested party replied that they had no comment. One interested party did not respond despite efforts to contact them. Any changes as a result of the submissions have been included in the final report.

- On 25 July 2024, the Commission approved the final report for publication.

Glossary Kuputaka

- Abeam

- At right angles to the helicopter’s line of flight.

- Anchor

- A heavy device (normally steel) designed as to grip the seabed to hold a vessel in a desired position.

- Anchor pulpit

- A protrusion at the bow of a boat designed for securing an anchor.

- Astern

- Referring to a vessel’s engine moving the vessel in reverse

- Give-way vessel

- Under the collision-prevention rules – a vessel that is directed to keep out of the way of another vessel

- Helm

- The means, such as a steering wheel, by which a vessel’s steering is controlled.

- Water ingress

- When water makes its way into the boat through a leak or crack

- Master

- A licensed mariner who has command of a merchant vessel

- Medevac

- Medevac is the transportation of patients from the accident site to a medical facility.

- Port

- The side of a vessel that is left when facing forward

- Service speed

- The normal operating speed of the vessel while in service

- Skipper

- The captain of a boat or ship

- Stand-on vessel

- Under the collision-prevention rules – a vessel that is required to maintain its course and speed and monitor the give-way vessel.

- Standing orders

- The rules posted by the vessel’s captain and/or the operator to be understood by each watchkeeper operating the vessel

- Starboard

- The right side of a vessel when the viewer is facing forward

- Wheelhouse

- Enclosed area on a ship from which it is steered

Appendix 1. Table 11 from Maritime Rules Part 31

Appendix 2. Maritime Rule 23.27

Appendix 3. Maritime New Zealand guideline – Single handed operations carrying passengers